Repertory Dance Theatre’s Emerge, which opened last night, is a series of little experiments, the stuff of which all good dances are made. Exemplary of a sense of play is company dancer Jaclyn Brown’s Trifle, in which she partners her non-dancer husband, Terry Brown. I didn’t see Jaclyn’s earlier work with her children, but I’ve seen many dances in this vein, from David Dorfman’s Family Project to Victoria Marks’ work with veterans. This trope can sometimes reframe the trained dancer, making them more interesting to watch. Occasionally, the tables are turned, and the so-called professionals are given a run for their money.

Luckily both Browns are compelling performers and are even more compelling as a pair. Terry has a presence and talent unusual in the context of this shtick. Paired with Jaclyn’s comedic timing, this makes the piece worth watching both as pure choreography and as a study in what a dancer is or isn’t. The sharing of weight in Trifle evinces the listening required in a real life marriage. It’s refreshing to watch Jaclyn try to catch her husband off balance, and the simple motif of Terry squatting down as he mirrors his wife in traveling steps is humorous, endearing, and well-developed. For once, it’s the man who’s doing everything backwards, if not in heels.

MASC (part 2), by Dan Higgins, is perhaps the most ambitious piece of the evening, at least in terms of length. As the lights come up, painted white and corseted in gold, Higgins, Kaya Wolsey, and Micah Burkhardt swing their hips to a series of clubby tracks that mix electronic sounds, Afro-Latin drumming, and a disconcerting text about conquerors on the beach, pockets full of sand, and casual drug use. Is the commentary here meant to be about the history of colonization? (The performers appear to be white as well as being painted so.) Is some idea of sexual liberation at stake? What is all the unison about? MASC is amply rehearsed, but like its score, feels full of mixed messages.

In both MASC and artistic associate Nicholas Cendese’s Tsvey Fun a Min, I feel like the choreographers are trying to communicate something very specific with their costuming choices. And sadly, in both cases, that something totally eludes me. Cendese’s piece makes use of boisterous Yiddish songs by the Barry Sisters, whose music you might recognize from the TV series The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel. A fifties-era, ostensibly heterosexual couple gambols amiably around the stage in period garb. The man (Daniel Do) is in a dress and the woman (Megan O’Brien) is in a boyish pair of overalls. Here the reversal is straightforward. In MASC, all the make-up, latex, and swooping limbs of a Gaga dancer lost at Burning Man amount to a big question mark. In neither case can I figure out what the choice to queer the obvious costuming is supposed to do to the choreography.

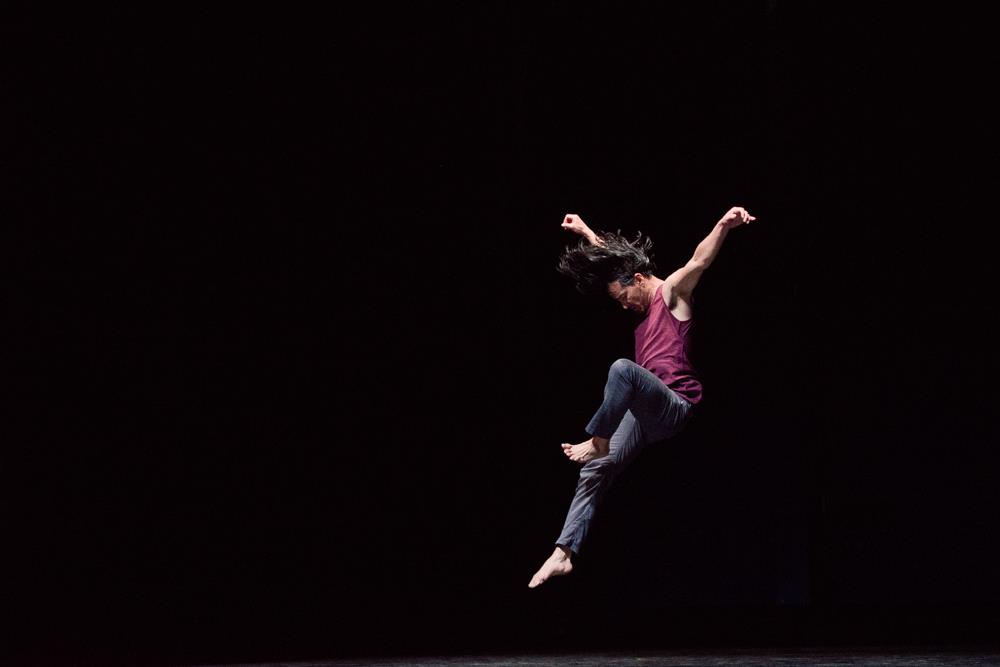

The highlight of the evening is Navigation, RDT artistic director Linda Smith’s solo for retiring dancer Efren Corado. Smith pieced together the solo with movement from some of the dozens of roles Corado has performed over the last six years. Corado nimbly samples the hairpin weight shifts of Limón and Cunningham, the exuberant footwork of Bill Evans, and much more that I couldn’t immediately place. All the while he navigates a grid of white Styrofoam boxes that cover the black marley floor. What we end up seeing is Corado’s nuance and endless reservoir of characters. He jumps, turns, and skitters, never once upsetting the take-out delivery boxes that mark out the arena. Rarely have I seen a solo so lovingly made for a specific performer. I’m not sure I could imagine anyone but Efren performing this dance. Like the chairs in Pina Bausch’s Cafe Müller, the boxes add a special absurdity to Corado’s gambit through the thousand and one choreographers. It’s like watching your favorite fictional detective (for me, Helen Mirren in Prime Suspect) give a final soliloquy while driving her car through an obstacle course. And the end, well, I won’t spoil it for you if you haven’t seen it yet…

Repertory Dance Theatre’s Emerge continues today, Saturday, January 5, with a matinee at 2 p.m. and a final evening performance at 7:30 p.m.

Samuel Hanson was born in Salt Lake City in 1988. His recent work has been seen in NYC at Triskelion, the Reckless Theater, Weis Acres, Green Space, Danspace through the Movement Research Festival, and in Utah at the Rose Wagner Center and in the Mudson performance series. He has performed for an eclectic mix of artists including Isabel Lewis, Yvonne Meier, Ishmael Houston-Jones, Mina Nishimura, Alexandra Pirici, Ashley Anderson, Diana Crum, and Yve Laris Cohen.