Repertory Dance Theatre presented the evening-length Dabke, by Zvi Gotheiner (choreographed initially on Gotheiner’s ZviDance in 2012), for the second time to Utah audiences. After performing an excerpt of the work in 2015, RDT premiered the full piece in 2017. This performance distinguished itself further in the more intimate Leona Wagner Black Box Theatre, which served the emotionally charged piece.

Much that is central to Dabke has already been written about and explored; among local writers Les Roka and loveDANCEmore’s own Liz Ivkovich, as well as New York-based writers Alastair Macaulay, Pascal Rekoert, and Brian Seibert, I will try to find my own voice within an established narrative.

Much has also been said about Dabke in terms of cultural appropriation, regarding who may lay claim on the dabke - the national dance of Lebanon, Jordan, Syria, and Palestine - or who (if anyone) may stake a claim on any cultural dance form. I came to the show with swirling dialogues of culture, power, and ownership, but also with a deep desire to watch and be moved by dance. Post-show, dialogues of cultural appropriation continue to swirl; notwithstanding, I was deeply taken with the power and complexity of Dabke and RDT’s embodied, virtuosic performance.

Dabke is Arabic for “stomping the ground” and this is how dancer Efren Corado begins. It is as if he is experiencing a memory, brought on by summoning a familiar beat within his body. When Lauren Curley tries to join him, he succinctly and somewhat aggressively denies her permission and continues alone. Eventually, the full company enters the space, but whether because of choreographic intent or personal performance quality (or both), Corado continues to be the central character. He is the sun and the others orbit around him, warmed by his energy.

The piece continues with entrances and exits, and with solos and duets that meld into larger group sections. A solo by Justin Bass marks the beginning of a musical score by Scott Killian, with dabke music by Ali El Deek. Bass is rounded and sensual, hips swaying and gestures soft. The solo recalls Gotheiner’s reference in “Creating Dabke” (an introductory film shown before the dance) to the quest to be “macho” in a hyper-masculine world. In one moment, Bass embodies the social construct of femininity; in the next, he is externally focused and direct, punctuating clear lines and rhythms in the space while referencing a cultural dance form that has often kept women from participating.

The struggle to preserve previous establishments is again communicated when Dan Higgins pulls at, then manically re-adjusts, his shirt. It is a gesture that hits an emotional chord and provides a pedestrian moment, a respite from the movement-driven work. Higgins plants himself downstage, his focus outward, while a group of dancers upstage, dimly lit, perform as if within his own mind. He lets the thoughts (dancers) play out, then walks off the stage without looking back.

The anchor of the evening is a solo (a duet, if you count Lacie Scott’s prone body) by Corado, in which he removes his shirt, wet with sweat, and proceeds with many actions rife with metaphor. He waves the shirt in the air, carefully arranges it on the floor in front of him while he kneels behind it, wraps it around his wrist - the shirt is both his offering and his lifeline.

Corado shines in roles such as these, roles in which the dancing may be important but the storytelling even more so. He has a vulnerability and a distinct self-awareness while losing himself that is piercing. Before this section ended, I found myself wishing I could restart it in an attempt to memorize every nuance. Eventually Scott joins Corado, partially undressed, in solidarity, but the moment reminds me that a woman removing her shirt carries a different weight than a man doing so.

There is violence in Dabke: aggressive partnering, convulsing bodies that won’t be quelled, imagery of slit throats, and coarse sexual gestures. While the piece is about coming together and being pulled apart, and ultimately about finding an experience in blended cultural forms, it is marketed as highlighting national and tribal identities, grappling with conflict in the Middle East, and as a hope for eventual peace.

I do not question the power of the moving body (in most respects), and certainly this work does well to explore, succinctly and powerfully, a myriad of themes central to the human experience. I do, however, question the ability of the moving body to stand in as a surrogate for a mass of countries with many distinct religions and cultures. Can we, as a community in Salt Lake City, not only appropriate a cultural dance form but also represent a complex war, with involvement by our own government to varying degrees? I do not propose to have the answers, but I do have many questions.

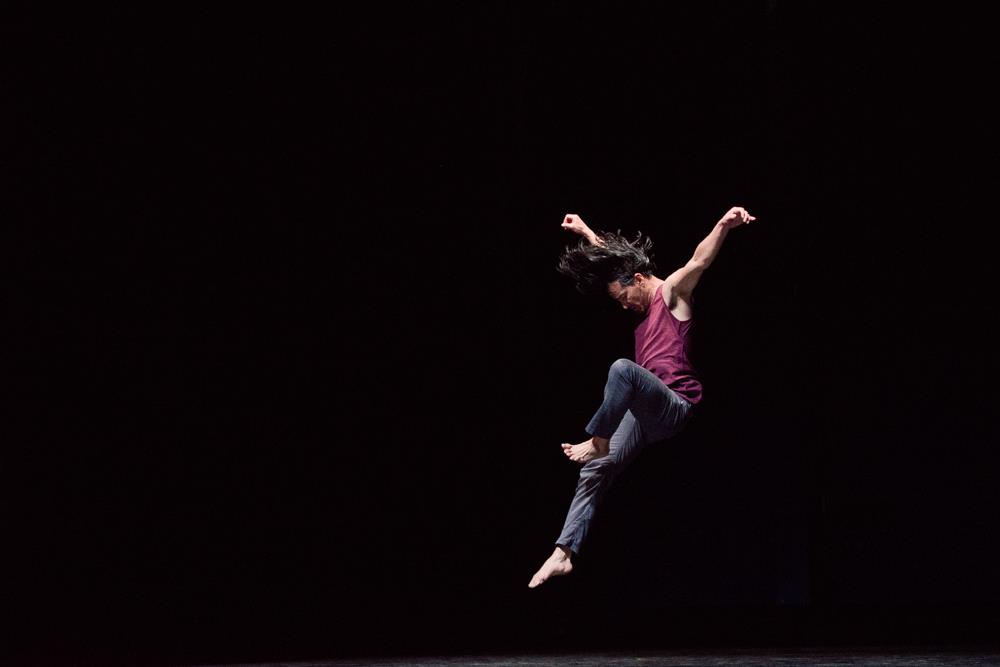

Ursula Perry has the last solo of the night. While the music relentlessly carries on, she struggles to find solid ground. She is beautiful and strong, then broken and weak. She clenches her fist as if she has found “it,” but then just as quickly lets “it” go. Sound escapes her mouth, jarring in its evidence that she and the others on stage for the past hour have been living, breathing people. She runs in circles, tracing the patterns that her community of dancers once traced with her. She is running, alone; she pants and gasps as the lights fade to black.

Ursula Perry in Zvi Gotheiner's Dabke. Photo by Sharon Kain.

Erica Womack is a Salt Lake City-based choreographer and an adjunct faculty member at Salt Lake Community College.