Sample Tracks, presented at Sugar Space Arts Warehouse, featured a compilation of varied artists from the community – just a bite of each. I attended Friday for the “B” program, which featured works by Sonali Loomba and Katie Sheen-Abbott, Fiona Nelson, Temria Airmet, and Aileen Norris. (Thursday night’s program highlighted the work of Cat + Fish Dances, Abbie Simpson, and Rebecca Webb.)

A demonstration of Kathak and flamenco opened the program, the first form hailing from northern India, the second arising in the south of Spain. “Passion for Percussion” illustrated the common language of these two dance forms and their accompanying musical traditions by placing them side by side. Sonali Loomba and Katie Sheen-Abbott were joined by Abhishek Mukherjee (sitar), Debanjan Bhattacharjee (tabla), Jake Abbott (guitar and vocals), and Sandy Meek (guitar). The musicians were as central as the dancers, in keeping with the leveled partnership between song and dance in both traditions. They started the night with an incredible display of technique enmeshing the two styles, each soundscape a perfectly suited complement.

Loomba and Sheen-Abbott didn’t fuse their styles as the musicians did, rather each performed their technique in turns, first to their music, then the reverse, before appearing together to perform nearly the same sequences side by side. It was an extremely effective demonstration. Twisting palms attached to undulating arms, twirling skirts, rhythms of the feet and the heels or bells to accentuate them, upper body held upright and forward, intensely expressive and directive eyes illuminating the surrounding space. Both dance styles are centered on expressive storytelling through codified imagery created by the upper limbs, while the feet keep a lighting-sharp and playful dialogue running with the musicians, whose instruments and compositions are uncannily alike. Or maybe not so uncannily – Jake Abbott briefly mentioned the historical development of flamenco out of Indian traditions, a relationship I hadn’t considered before that now seems a curious and obvious probability to look in to.

The program note for “Semblance” by Fiona Nelson referenced “illuminated faces, phases of the moon, memory, duets in time and space” and a Mark Twain quote – “everyone.. has a dark side which he never shows...” These referents remained somewhat nebulous in relation to the choreography. Black costumes and stark, single-sourced lighting sort of invoked moonscapes, but my mind mostly wandered into aquariums and their dark neon-infused jellyfish rooms as I watched. Side to side, circling, rising, falling, pausing, passing, the dancers maintained a flatly dynamic liquidity suited to the circular twinkly drones of the music. Bright white and subtle green lights overhead reflected off drifting skin surfaces, the particulars of choreography becoming something passed over for the pleasant haze of a windmilling ebb and flow.

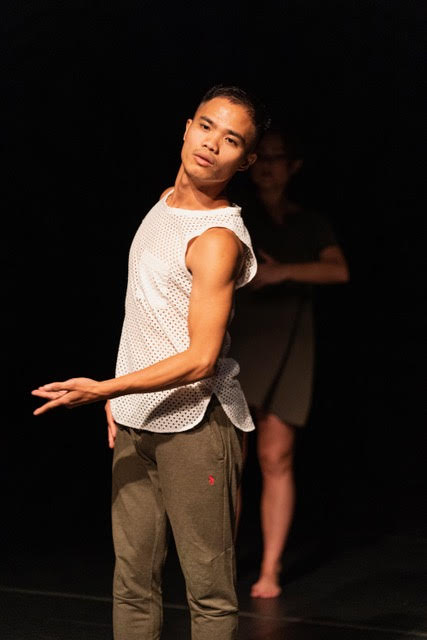

Third on the program was a solo performance by Temria Airmet. As in previous works, Airmet took a very large bite at a contemporary political topic (this time, “the current societal movement of feminism” and #metoo), attempting to distill nuance and context to a pithy minute drama with an uplifting final cry. Spreading a large bolt of white tulle across the stage, Airmet began a monologue on her version of feminism, religious doctrine from her youth and its impact on her self-perception, personal traumatic experiences, and a quick list of some topical social and political crises. She shuffled around in the tulle, punctuating her story with interpretive gestures and two more dance-y interludes, the first to a glitching dream-pop track of unknown origin (for some reason Airmet’s was the only piece on the program to forgo musical credits) and the second to David Bowie’s “Space Oddity.” The piece ended with the fist-shaking cry that “this revolution... is working.” Which is fine and good and perhaps true, sometimes, except that in many places and for many people, it is also not.

The final work, by Aileen Norris and dancers Alexandra Barbier, Arin Lynn, and Emma Sargent, was “The Convoluted Love Ballad of V___.” Tracing something unseen, Sargent was soon joined by Barbier, Lynn sliding in unnoticed upstage. The three spiraled into each other, becoming entangled and entranced in turns. When the music turned to sloshing ocean sounds, they became isolated rocks in its currents, static and shifting in turns until Barbier and Lynn fused together. From there it got... convoluted. The three slid in and out of complicated loves and betrayals; the movement was loose, swinging, and easy. Smiles were a treasure, then a dagger. Nico crooned overhead in a track about a dangerous femme, and when the rushing water returned, all three were linked, pushing, pulling, pushing, pulling in the same direction.

Photo of Temria Airmet at Sample Tracks by Laura De Backer.

Emily Snow is a Denver native who now calls Salt Lake City home. She has most recently been seen performing with Municipal Ballet Co. and with Durian Durian, an art band that combines electronic music and postmodern dance.