"Anything is possible once enough human beings realize that the whole of the human future is at stake." The words of Norman Cousins, American activist and peacemaker, echoed over and over in Jessica Lang's “us/we.” A farewell piece for her company Jessica Lang Dance (which is currently on its final tour following an eight-year run), “us/we” was the first on a diverse program presented by the Ogden Symphony Ballet Association at the Val. A Browning Center this weekend.

A delicious visual experience, “us/we” was a series of snapshots that zoomed in and out on Brooklyn, New York. The piece, created with visual artist Jose Parla, featured colorful projections that filled a screen upstage, framing the dancers and at times covering them with projected light. In a phone interview last week, Lang spoke with this writer about the "layering patchwork" of “us/we.” "It's all tied together," she said, which became clear throughout the driving work.

The set included three large pieces of fabric hanging upstage, each piece mapped for specific images. In the first section of “us/we,” the dancers wore costumes made from cloth used by Parla during his painting process, which was captured on camera and then integrated into the visual design. Still images of his completed works were also used. Costume designer Moriah Black constructed a second set of costumes by piecing together graphic-heavy items found at thrift stores from all over the world.

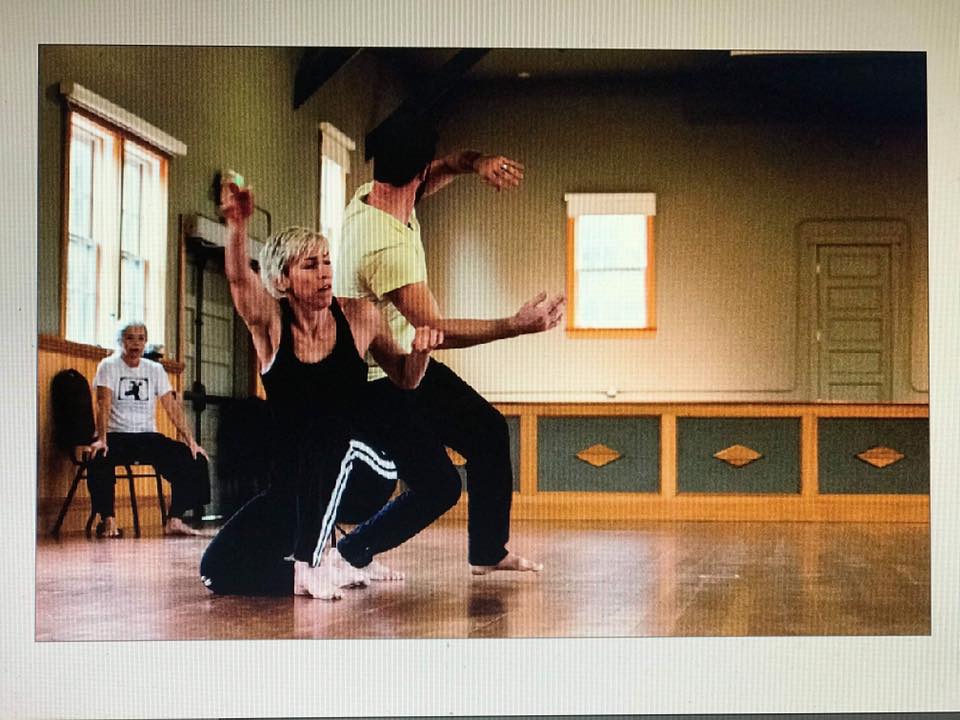

“us/we” spoke to a sense of unity by joining different people, places, and histories, and resonated through the dancers, who didn’t spend much time standing still as they moved between club scenes, busking scenes, and many literal tableaus, and incorporated gestural movement resembling American Sign Language. Notably, the piece coordinated large groups for impressive, multi-person partnering that had a flair for the dramatic, blending ballet and cinema.

The snapshots of “us/we” moved quickly, transitions almost nonexistent between a dance scene set to Ram Jam’s “Black Betty” and a moodier contemporary sequence. Quick changes of pace, glimpses into relationships, and hints at iconic moments recreated the feeling of riding public transportation: I remembered visiting New York for the first time, and the thrill of watching the city rush by on the subway as my face pressed against the window.

After speaking to Lang about “us/we” and then experiencing it, I see it as a love letter to the company: It is the last piece Lang will have made with the dancers, before all move on to the next stage of their respective careers. Near the end of the piece, the dancers appropriately sang “Can't Help Falling in Love.” With crescendos and brief moments of quietude, “us/we” was a lovely symphony of New York, and by extension, the world.

As a presenter, I would have opted to complete the concert with “us/we,” leaving the audience with a sense of connection and desire for more, instead of ending as the show did with “This Thing Called Love.” In contrast to the rest of the program, the fun, swingy Tony Bennett tribute paled in comparison in both content and complexity. The superimposed emotional content of “This Thing Called Love” was also amplified by its placement on the program following “Thousand Yard Stare” and “The Calling.”

Arguably Lang's most recognizable work, “The Calling” is a beautifully clear haiku of isolation and longing. Julie Fiorenza performed it with articulate grace and a length that defied that of her actual limbs.

“Thousand Yard Stare” always catches my breath. There is something about the way the dancers need each other that speaks to more than just the grit and grief of war. It also speaks to a cultural grappling with loss.

When the dancers moved through the exposed stage, the wings and scrim removed, they were in clear relationship to one another, coming in and out of unison, their contact characterized by dependence. They reached, fell, and collided, moving through space as if it was dense with fog and resistance.

Compositionally, “Thousand Yard Stare” was the most readable of Lang's work on the program. In it, she repeated and recreated scenes spatially as well as gesturally, making it easy to telecast personal or imagined relationships onto the dancers. There was a moving moment when a dancer was left out of the fold, powerful because the dancers were rarely alone throughout the piece. Their mass of overlapping bodies quickly pulled her back in, lifted her over their heads, and, surprisingly, tucked her in between them as if placing a baby bird back in its nest.

It is easy to imagine why “Thousand Yard Stare” is one of the company’s most performed pieces. Set to Beethoven's String Quartet No. 15, Op. 132, its music and movement swim together in hope despite the inevitability of death.

The dancers moved as a unit, offering the audience a sense of humanity and redemption. It would be easy to make a dance that captures the brutality of war, but for “Thousand Yard Stare,” Lang was interested in a different approach. ”We still have to carry hope," she says. She chose the music in part because Beethoven wrote the piece while he was dying, looking at the end of his life. Lang’s care and empathy are visible throughout it, and it’s a piece that does for me what I aspire to do for others through my own dance-making: It softens me, nudging me toward an understanding of the things I do not know.

I inquired about Lang’s plans for the future, now that Jessica Lang Dance is completing its final season, and why she is dissolving the company: She intends to keep creating work independently. Managing a company required her to spend less and less time working in the studio, and more time performing administrative tasks.

It’s clear that working with the same group of dancers for nine years has given Lang the freedom to push the boundaries of her aesthetic. I admire her choice to dissolve what many may think of as the pinnacle of success in order to continue pursuing the complexity of her craft. Now, she will take what she has gathered from Jessica Lang Dance and move forward, making new dances with new collaborators. “There are other things I want to try,” Lang says, and her decision reminds me that we can always change paths, make new choices, and dig deeper into that which inspires us.

Originally from the Midwest, Hannah Fischer is currently pursuing her MFA at the University of Utah. She received an Individual Artist Grant through the Indiana Arts Commission in 2017 and was an Associate Artist-in-Residence at the Atlantic Center for the Arts in 2014.