On December 21, the sun set in Salt Lake City at 5:03 p.m. Normally this, the shortest day of the year, reminds me of my desperate need for more sunlight (if you’re like me, you may want to check out a seasonal affective disorder light, which helps to combat the winter blues). But this year, the Heartland collective invited us to celebrate the winter solstice with them at Cosmos, a performance and dance party at the Utah Museum of Contemporary Art (UMOCA).

The date of the performance was no coincidence. The winter solstice holds significance in many indigenous cultures and various religions as a celebration of the longest hours of darkness. Winter is about to begin, but hours of daylight also are about to begin lengthening, and the solstice is a time to embrace reflections upon and rituals of regeneration and renewal. The evening, curated by director Molly Heller alongside her troupe of Heartlanders, was dedicated to this kind of communal reflection.

As I entered the museum, the walls, normally illuminated to highlight galleries, were darkened. A kaleidoscope of rainbow light was strewn across the space, resembling the aurora borealis. Inside a gallery, two benches were filled with dozens of handcrafted silver boutonnieres for guests to select. I was delighted to admire each tiny piece of charming art and to select one for myself to pin onto my clothing. Cosmos also then invited me to have my face bedazzled with silver jewels. This was a theme throughout the evening: attendees were continuously invited to participate, becoming part of the art themselves.

Nick Foster and Michael Wall entered the upstairs gallery, both wearing shimmery, silver tops, and filled the space with serene sounds that carried the evening from performance to dance party and on the journey in between.

Florian Alberge, an unbilled surprise guest who recently moved back to Salt Lake City, invited the audience to write a letter, beginning “Dear Closure,” that would be burned by the Heartlanders on New Year’s Eve. This idea calls upon the tradition of a fire-releasing ceremony, often practiced on the winter solstice, where what is desired to be released is first written down and then burned as a symbol of closure.

Heller has noted her fascination with closure: “The vulnerability within letting go and in allowing closure to be non-linear and self-actualized is what we’re exposing within Cosmos. I am discovering on a personal level that healing/release can happen with strangers and if we can’t choose our endings in life, we can practice curating beginnings.” Throughout the evening, attendees were offered many opportunities to explore such ideas of release through writing, witnessing, and dancing.

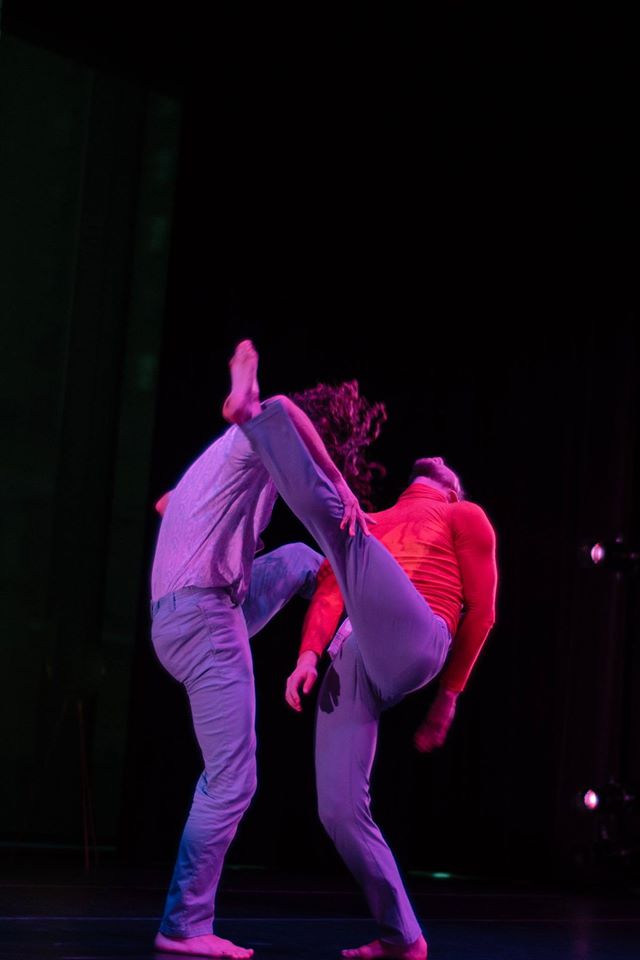

As the performance continued, attendees outlined the long row of windows that look down upon the lower-level galleries. Heartlanders Nick Blaylock, Brian Gerke, Molly Heller, Marissa Mooney, and Melissa Younker entered and began diving in and out from the gallery walls, like atoms vibrating, darting, and pivoting. One person remarked what a magical fish bowl we were peering into, as we witnessed the Heartlanders expand and contract throughout every corner of the space.

One of the most striking moments began as Blaylock took off in a full sprint and dove to the floor, sliding nearly twelve feet across the gallery. The rest of the performers soon followed suit. There was something so whimsical and playful as they slid with such vigor in between the gallery walls that still displayed art by Cara Krebs and Stephanie Leitch, among others - all while wearing silver vintage costumes. It was a dazzling juxtaposition that brought a smile to my face.

We were soon invited down to wander the lower galleries. In a moment of delightful surprise, the side garage door (normally used to transport large works of art in and out of the gallery) opened and the Heartlanders re-entered in a series of repetitive, quirky gestures. Foster and Wall transitioned into a whimsical, carnival score. A mist of whispers filled the space: “How fun!” “How exciting!” “How wonderful this all is.”

Heller began to give verbal instructions; attendees and Heartlanders alike participated in an improvisation score that spread throughout the space, the instructions guiding everyone first to spin on an axis, then to prance through the feet. It was a carefree, unpretentious, and shared sequence. An attendee later expressed, “I felt like I was inside of this world and the characters were unraveling right in front of me. It was exciting to be in the middle of the chaos and also inside the resolution.” The model of Heartland events is unique in this way - it interweaves performers and attendees in such a way that facilitates a shared experience. You do not simply watch a Heartland event; you become a part of it.

As performance bled into dance party, everyone began to jump, shimmy, spiral, wiggle, sing, and bop together. Heartlanders swirled throughout clusters of attendees, sharing hugs and inspiring new dance moves. One attendee remarked on the palpable shared energy. It was fun. It was tiring. It was meditative. In a darkened museum on the winter solstice, we jammed out together, sweating through our shimmering clothes.

Heller’s work has long been dedicated to her research of performance as a healing practice. It felt important to me that this performance-cum-party took place in such a shared setting. I found myself deep in thought about the role of community in supporting the health and wellbeing of ourselves and those around us. Heartland events have introduced a very special ritual to the community for these reasons.

Those that stayed until the end witnessed Younker, Heller, and Mooney sing and shout a manifesto dedicated to release, healing, and closure. Attendees shouted along (even when we didn’t know the words), and I couldn’t stop myself from bouncing and clapping. The evening ended with catharsis, in the presence of friends, strangers, and glittery boutonnieres.

Rachel Luebbert is a Utah-based dance artist. She also teaches and works in arts administration and programming, and has previously worked in Colorado, Massachusetts, and Washington, D.C.