Molly Heller’s “very vary” was just that: a very varied patchwork. For the duration of her hour-long dance, the cast of six - both members of Ririe-Woodbury and freelancers alike - approached Heller’s performatively demanding work with integrity.

Papier-mâché animal heads by Gretchen Reynolds lined the back of the stage, glowing orbs lit from within. According to the program, each performer identified with one of these six animals: a bee, a deer, a monkey, a lion, a wolf, a seahorse. The only decoration in the Eccles Regent purple box, the animal heads added a minimal yet detailed touch, and I looked forward to how the performers might further define relationships to them.

The opening section was organized chaos, the dancers slotting into varying identities from the start. The Pixies blared; Florian Alberge yelled, Mary Lyn Graves did a mockingly good petite allegro routine, and Marissa Mooney burped (this elicited laughs, but I could have recognized Mooney’s derring do in spite of this). Melissa Younker’s innocent inquisitiveness stood out to me; her character quietly explored a landscape that the others often experienced more explosively.

Much of the physical vocabulary in “very vary” was fresh to my dance-worn eyes. The dancers’ movement came in spurts and appeared image- or emotion-driven (rather than dance for dance’s sake). The quick darts between movements and also sections managed to maintain a certain logic in their dissonance.

While there were many compelling moments by each of the six dancers, I did find that some entreated their rites and plights more truthfully, or at least less forcefully, to me than others. Some arcs of investigation I read as honest, and even vulnerable; others verged on feeling put upon, or done for the sake of performance.

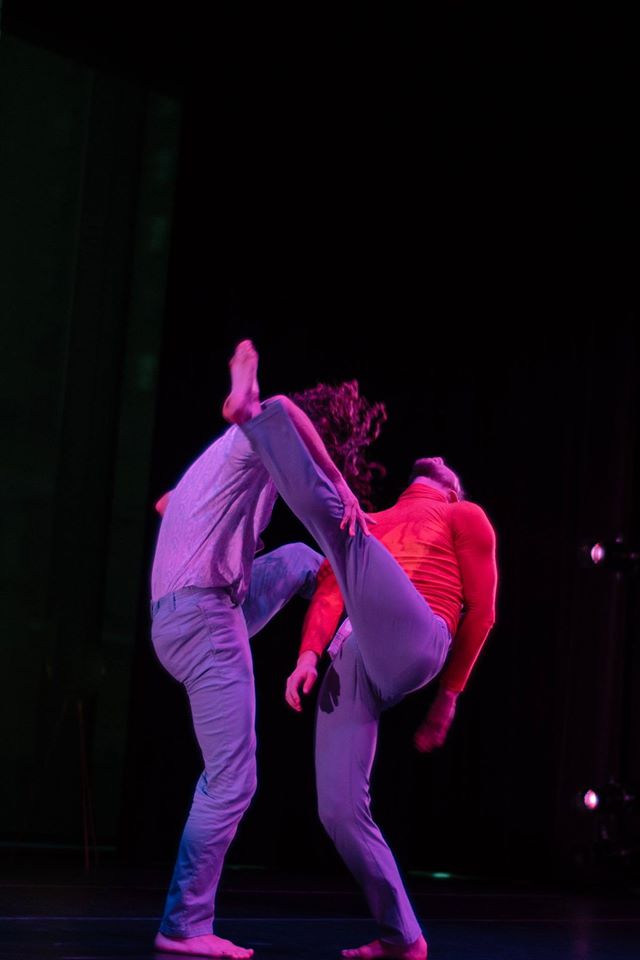

Physical humor triumphed. Alberge and Nick Blaylock had a duet to Elton John’s “Rocket Man” that was a hybrid of slapstick and modern dance, timed masterfully.

"Rocket Man" duet with Florian Alberge (right) and Nick Blaylock. Photo by Tori Duhaime.

Mooney introduced a different brand of physical humor. Telling a story about a crowded train, she noted that overhead luggage should be placed in the overhead bins - as Alberge’s dancing body was implicated as the luggage. As the group wrestled her overhead in a tangle of their arms, Mooney spoke of feeling trapped. The humor in such parallels between the spoken and the physical was successful for me.

Near the end of the dance, the opening “chaos” section was reprised, with dancers swapping roles. Graves punched through what was originally Yebel Gallegos’ serious boxing routine. Sometimes the do-er fit seamlessly into the newly assumed role; other times, the do-er appeared to have donned ill-fitting clothes. In either case, adopting others’ identities was an interesting progression after seeing each performer make their own brand of choices for most of the dance.

The dancers then helped one another tie the glowing animal visages to the tops of their heads; each seemed to have come to terms with both himself and others, and was now able to exist singularly as well as collaboratively. I wondered whether the preceding parts of the dance offered ample segue to this conclusion, and additionally wondered about the connections to the specific animals each performer supposedly had.

The dancers and their animal heads. Heads by Gretchen Reynolds, photo by Tori Duhaime.

Some of my favorite moments were when the dancers traveled around the stage en masse, like a whimsical marching band. The first time this happened, Younker conducted them as they quietly raged on their imaginary instruments; as she yelled “Louder!”, I couldn’t help but picture Spongebob Squarepants' compatriots, led by clarinet aficionado Squidward in a madcap dash around Bikini Bottom.

The second time, having donned the glowing heads, the dancers alit for a final lap. Like a mystical gaggle of Hayao Miyazaki animations, they floated, dream-like, past us before their departure. The final image presented itself to me as a reflection, in the back windows which opened mid-dance on a perfect, lilac dusk. Now, as dusk turned to night, the magical creatures began to make their way to their next engagement. I watched the reflections of their glowing heads recede as they filed, one by one, out the back.

This conclusion was lovely and evocative, but hard work for me to connect to the rest of the very varied material. Instead, I found myself waiting for the night animals to come out to play, wishing they had sooner. The ending of this iteration of “very vary” worked well as an epilogue, but might still be missing its final chapter.

Amy Falls is the development coordinator at Ballet West and loveDANCEmore’s former Mudson coordinator.