Ririe-Woodbury Dance Company’s Bloom featured two new works, one by artistic director Daniel Charon and one by University of Utah professor Stephen Koester, as well as a piece by Tzveta Kassabova (2010) that Ririe-Woodbury first performed in 2016. The concert was well-formatted, with Charon’s dynamic and daring work splicing two more humanistic explorations of relationship and transition. I’m not convinced the title Bloom accurately described my experience, but how does one accurately name a diverse repertory program? If the title didn’t portray what was happening on stage, it did sum up the beautiful Salt Lake City spring that is happening outside.

Kassabova choreographed “The Opposite of Killing” as an exploration of emotions pertinent to losing a close friend, and the piece has been performed by multiple casts, including by students at the University of Florida, University of Maryland Baltimore County, and Middlebury College. Amy Falls did a thorough job of describing and unpacking the piece at its Utah premiere; I will add that I especially found meaning in its arc.

The beginning was an exploration of movement, absence of movement; sound, absence of sound. The dancers confidently found their places making parallel lines and right angles, clear in their mission and devoid of emotional ambiguity. As the piece unfolded, it slowed down, weighted with grief. Breeanne Saxton found herself upstage and alone, bathed in a warm spotlight, isolated, watching the movement carry on without her.

There were the more obvious moments of experiencing loss, such as soft embraces and collapsing bodies. Particularly resonant, however, was the constant shift of dancers’ costumes. As the choreography moved the dancers on and off stage, each subtly shifted what they were wearing; one who was wearing shorts came out in pants, one previously showing skin next appeared in a turtleneck. The costume changes never departed from a gray palette, but morphed enough to signal that each dancer was, in fact, changing; as if to say, “I may be similar on the outside, however, with loss, there is a shift.”

The end was the beginning, the dancers lying down in horizontal and vertical lines. What felt self-assured and expectant in the opening scene now felt unresolved and heavy. What we experienced in the middle shifted everything.

Charon’s Dance for a Liminal Space, divided into two parts, buffered either side of the intermission, and each part diverged from the other in their definitions of “liminal.” From the program notes, the first section related to a transitional or initial stage of process, while the second explored occupying a position at, or on both sides of, a boundary. I found both parts showcased the five dancers beautifully (Brian Nelson, who joined the company in 2018, did not appear in the piece), as well as challenged notions of how to convey something both in transition and arriving from transition. That is to say, I liked it.

The first part began with the three women of the company (Megan McCarthy, Melissa Younker, and Breeanne Saxton) as clear, directional, and undulatory, their bodies bright and severe against the darkness of the stage. Then, just when I started to put my finger on the piece, text by Meredith Monk began. Phrases such as “he salted his empty plate first” and “she wears the same bow as her dog” refused to relate to what was happening on stage, and scrambled any definitive meaning. This absurdity paired with the robust physicality was oddly satisfying, and forced my mind to open and receive instead of to close and define. Undoubtedly, there will be those that find the disparity jarring, even frustrating; but when the closing image was settled and fixed, two groups having taken their places, statuesque and clear, I appreciated it even more.

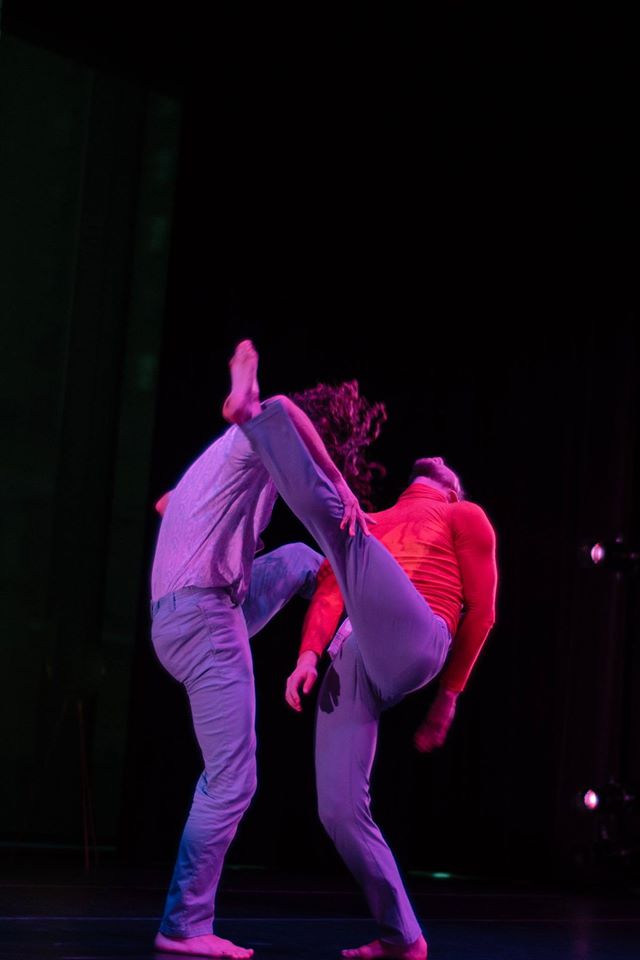

The second part of Dances for a Liminal Space was highlighted with bold and geometric lighting by Ririe-Woodbury technical director William Peterson and relentless music by Michael Gordon. Did I mention that the dancers looked fantastic? Because they did. Bloom is also the farewell concert for both Yebel Gallegos and Breeanne Saxton, two versatile dancers that will be greatly missed. They, along with the others, were in perfect form, and this section of Charon’s piece in particular showed off the company’s range and virtuosity. Bashaun Williams and Megan McCarthy travelled from one side of the stage to the other, flying, twisting, and turning, and when they leapt into the wings, I wished they would run back around and soar through the phrase again. The stakes were high in this section, the position had been chosen, and it was time for the dancers to confront the consequence with intensity and resolve.

The final piece was Koester’s “Departure - A Last Song, Perhaps a Final Dance Before a Rest.” As the program note detailed, Koester is retiring from his position at the University of Utah in the School of Dance, and perhaps from dance in general. I was his student at the U during graduate school, and thus feel a personal connection to his retirement; he has been a strong figure in the Utah dance community for decades. I have admired him as a choreographer, and found his pieces bold and impactful -- even the few that I did not enjoy would run through my mind for weeks after, as I tried to find a landing place for them (arguably the biggest compliment of all).

To that end, I found myself anticipating what his final work would be. Conceptually challenging? Movement-driven? Autobiographical? Trying not to be too melodramatic (although the piece’s title doesn’t temper this), it was as if we were all huddled around him, staring intently: “What are your parting words?!”

His parting words in “Departure” seemed to be, “Find community. Help one another. Be together.” The piece featured the entire company, clad in pedestrian clothes, with music by David Lang. There was form to it, but that form sprouted from relationships as each dancer seemingly took a turn at being supported, or at least seen, by the others. Sometimes the relationships poked, nagged, questioned, or insisted; there was little movement for movement’s sake, each vignette attaining an emotional resonance that could also immediately shift or drop.

The final image was a terse wave from Yebel Gallegos, as he and Brian Nelson retreated upstage, the lights fading.

Bloom concludes tonight, April 20, with a final performance at 7:30 p.m. at the Rose Wagner Center for the Performing Arts.

Erica Womack is a Salt Lake City-based choreographer. She coordinates loveDANCEmore’s Mudson series and contributes regularly to the blog.