Return, the third and final work of Daniel Charon’s “Together Alone” trilogy, premiered in the Eccles Theater's Regent Street Black Box. The space placed the Ririe-Woodbury Dance Company performers in a new and exciting venue, so different from their home at the Rose Wagner. The audience sat in the round, which created an intimate, circular gathering. As the dancers entered, they seemed just an arm’s reach away; their breath could be felt, and every step heard. All of a sudden, strips of light that surrounded the dance floor lit up, creating a tangible border - immediately, the dancers felt detached, separated from the audience. They began moving with a floating, eerie quality that was abruptly interrupted by flashing red lights and a booming voice yelling, “Warning! Warning!” The dancers quickly left the space. This shift added a taste of urgency and tension, mixed with a layer of science-fiction, to the scene.

The dancers then began subtle movement that grew larger to a percussive, intriguing score by the Salt Lake Electric Ensemble. There was a shockingly beautiful moment as Melissa Younker balanced precariously on Bashaun Williams’ leg as he lay on the ground. Her body swayed slightly, from side to side, like an upside-down leaf dangling from a tree.

As the movement became larger and more intense, a constant entering and exiting of bodies developed, eventually giving way to several solos, duets, trios, and larger group phrases. However, each section was brief and interrupted as the dancers quickly exited. These fleeting interactions never felt fully realized. There was a constant, dissatisfying resonance of something left unfinished. As I watched the dancers leap and dive with flying, suspended legs, the performance space felt cramped, like we were looking in on an enclosed environment that was too small, too tight. Yet this bound, constricted space appeared to be an intentional critique of the effect of technology tightening the space around us. The dance seemed to say, “If we are not careful, we will be boxed in by our own devices.”

The piece continued with incredibly dynamic shifts through space and stunningly embodied movement. At one moment, most of the dancers left the space and Yebel Gallegos performed an exquisite solo. As his body rattled and curved, small droplets of sweat sprinkled off of him and twinkled in the luminous light. This moment of splendor led into haunting text, each dancer sharing a single sentence, a fragmented idea: “We had to move on”; “It was hard to tell”; “We have to do it again.” Each carried an ambiguously eerie weight and evoked an apocalyptic scenario. Each dancer seemed to be adding a significant thought on to the last, but they never looked at each other or acknowledged one another’s presence. They seemed so very close together, but also distantly removed.

Later, the dancers stood on opposite edges of the floor, looking out into the audience with their backs to each other. Two dancers at a time would say the same text in a conversation that felt incredibly mechanical. One pairing of dancers wanted to discuss something but the other grouping continued to repeat, “I can’t, I’m expecting someone.” This pixelated conversation was broken and dysfunctional. A tension was created, as something important needed to be shared and communicated but no one knew how to do it. As an audience member, I felt a deep craving for this human interaction to be fulfilled, but the dancers remained separated and unable to complete the urgent conversation.

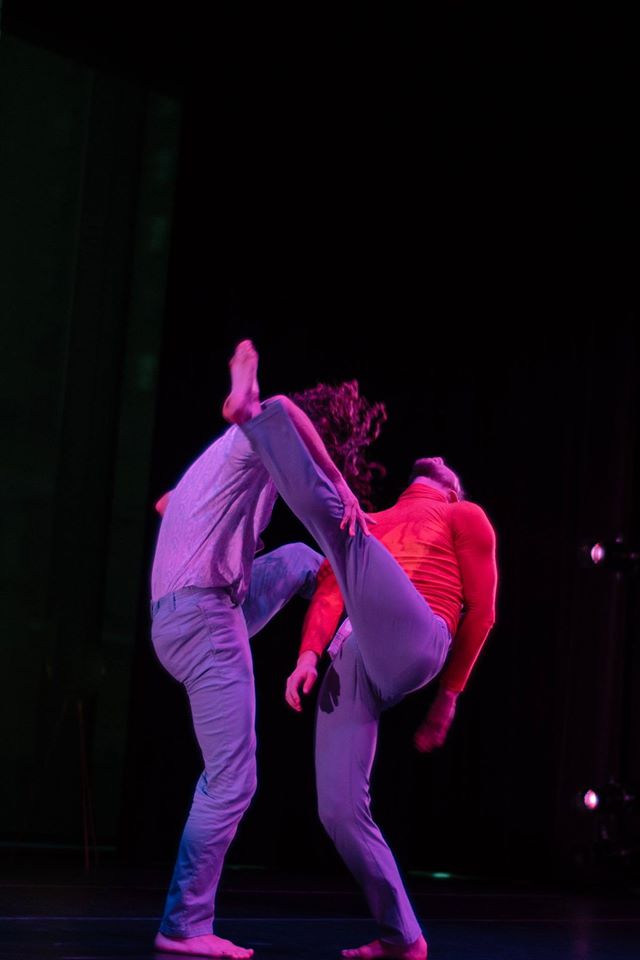

These moments of intriguing narrative were followed by deeply physical movement. Megan McCarthy and Gallegos had a breathtaking duet. Their bodies rotated in quick, tightly controlled spirals and their legs swirled in luscious circles that carried them to the ground in exciting sweeps of momentum. Return was Mary Lyn Graves’ last performance with Ririe-Woodbury and her dancing was also exquisite throughout the performance.

The costumes for Return were designed by fashion stylist Laura Kiechle, who created the many different looks changed into throughout the show. The costumes introduced new moods and textures throughout. The dancers began in grey and blue shirts and pants that were a blend of Star Trek and post-modern. Later, the dancers filtered back on in all-black costumes that featured an intriguing exposed square on each back. At one point, McCarthy wore a stunning, long peach-colored dress. The final costumes were blue shorts and white shirts that resembled swimwear from the 1950s. The constant changing of costumes continued to introduce a new aesthetic to a continual play of together- and apartness. There was a truly striking development in the way that new costumes were introduced; only a few dancers would change at a time, the new look slowly infiltrating the stage in pieces, as if through a shift in time.

One of the most striking moments was as Gallegos shared lines of text in Spanish: “No hay nadie más en el mundo. No hay nadie más en la vista.” Younker repeated the lines in English: “There is no one else in the world. There is no one else in sight.” The two of them walked along the edge of the lit square and repeated the lines with slight additions and variations. It was striking to watch the others move within the square and to feel their deep separation as Younker and Gallegos spoke about being alone. There was an incredible irony in hearing their call and response in different languages and their inability to connect with each other, or those moving around them - almost as if there was no one left in the world.

Throughout Return, Charon played with the way technology affects, and will affect, human interaction. In many moments, I felt trapped in an episode of Black Mirror. Return presented an impressive collaboration of movement, spoken text, sound, lighting design, and costume design to create imagery of future humans as disconnected beings that exist together, but are mostly alone.

Melissa Younker and Yebel Gallegos in Return.

Rachel Luebbert is a recent graduate of the University of Utah, having completed a dual degree in modern dance and Spanish. Rachel has also contributed writing to the College of Fine Arts’ blog, The Finer Points.