In addition to re-imaginings of company repertoire as well as happenings and installations throughout the year, SB Dance produces an original new work each June. Their latest, a two-night run of Sleeping Beauty at the Rose Wagner, contained many of the unique hallmarks that have developed with the company over its 20-year span. These hallmarks include intricate and energetic movement that retains the vitality of just the right amount of creation and rehearsal time, consistently deft prop and set piece incorporation and manipulation, interdisciplinary collaborations, thoughtful production choices, and representations of elements of queer identity. Also included is frequent reference to S&M, bondage, and sexual power dynamics. This could easily play out as a short-cut to dynamic tension, but it instead emphasizes charged human connection in the well-practiced and integral role it plays in SB works. Themes of consent as well as physical and psychological dominance and submission are modally fitting for movement-based theater. These very themes are subtextually quite present in existing classical interpretations of The Sleeping Beauty, and explicitly take center stage in SB’s retelling.

In the program notes, director Stephen Brown cites two books that re-engaged his interest in the “typically misogynistic classic.” One is Robert Coover’s metanarrative novel, from which Brown borrows the multiple-perspective approach of the different fairytale archetypes to frame the show. But the show is critically divergent in this way: Where the novel is postmodern in structural form, SB’s reverts to the classic storytelling device of explicit narration. This is an apt choice for the more abstracted media of interdisciplinary live dance theater. The narration is carried out with stagey charm by vocalist/actor Ischa Bea and string accompanist Raffi Shahanian, jointly billed as MiNX. These two serenade us in song and introduce the primary characters and their conflict: Annie Kent as Aurora and Nathan Shaw as Maleficent, in a dramatic first romantic encounter.

The introduction is an intense duet. Both characters wield a carving knife in each hand. The flourishing knives never supercede their interplay; they serve as an extension of the sharp, symmetrical movement quality. Annie Kent is instantly a compelling performer in the titular role whose presence reads well in the intimate black box theater, a space with effective technical production and unobstructed sightlines from the stadium-style seating. The audience gazes down on this private moment of consensual, equal powerplay; it is the show’s last. Maleficent alludes to the classic cursing pin-prick with a knife cut along Aurora’s skin, thus felling her. Aurora is put in her figurative box as an inert object of desire - by being stuffed quite literally into a cardboard box and loaded onto a dolly, which Shaw step-ball-changes, impressively lightly yet ominously, into the wings.

The next scene features four boxes, each containing a languid, sleeping someone in navy gender-neutral jammies - Aurora and the three Beauties, performed by Christine Hasegawa, John Allen, and Ari Hassett. Arms flop and butts lift from within as harpsichord strains evoke the Baroque, to great effect. These sleeping cuties re-emerge and re-enter their packages and sprawl onto their pillows in a very realized dreamstate, and momentarily make us wonder just what they’re up to in there. They begin to interact, and execute a catching and falling sequence into the pillows. Shaw then reappears to partner the dreamers. SB newcomer Ari Hassett sought her withheld pillow by avidly scrambling up Shaw into a high-flying press lift, to general gasps. She consistently displayed the great strength and agility of someone you suspect may be more comfortable inverted than not. Shaw packs them and stacks them, continuing the deft utilization of props with a believable slapstick drop of the topmost box before exiting to leave the lone packaged princess center stage.

The narrator next introduces and campily sexualizes Prince Phillip, played with hyperbolic virility and suavity by Juan Carlos Claudio. He distributes flowers amongst the audience in the single house-lights-up nod to immersive audience interaction. Then begins the beautiful and effective and creepy duet with a half-lucid, half-conscious Kent. I have been recently discussing the classical dance trope of the partnering of an exhausted/poisoned/dying woman a la Swan Lake, La Sylphide, etc., and was gratified to see it so explicitly treated here. The narrator jumps the gun with a “happily ever after”: As Aurora awakens to the Prince’s (steamy) nonconsensual attentions, she slaps him and heads out. Here the “reworking of a classic fairytale” metanarrative becomes central. The narrator frantically rewrites the story (adorably, with a feathered quill in a very contemporary libretto binder). Her accompanist, enjoined to “play something!,” delivers a cringily deadpan rendition of Sublime’s “Date Rape.” Directed to play anything else, he moves along to Eurythmics’ hit “Sweet Dreams (Are Made of This).” Tellingly, this is a shift from a direct naming of the violation of body autonomy to fantasies of dominance and submission. There is herein some precedent for the show’s glancing identification of abuse pivoting to the focal artistic treatment of desire and sexuality.

We next see Aurora striking out for L.A., a classic naive waif with tattered nighty, shawl, and old suitcase in tow. The former cohort of Beauties in forced slumber now become minions of their malevolent captor. They are intriguingly costumed in black, their bad-guy hats still sporting tags, Hassett in full mustachioed Groucho mask, all sporting bedroom slippers. This last addition made all the following choreography exceptionally interesting and beautiful - lots of fluid petite allegro and gliding undercurves. The three Beauties establish themselves as a compelling ensemble, whose different movement qualities mesh together in a cohesive whole.

This cohesion holds well throughout the knife-wielding dance led by Shaw in what seems to be a warehouse of the boxed. Shaw’s Maleficent grinds on the cardboard containing the Princess, gaining pleasure from his control. The Prince obsesses over the same object from behind a stack. The two begin a voyeuristic game of withholding and expressing proprietary power over the box, deepening their characterizations and dynamic tension. The captured and bound Prince must watch the sadistic stabbing of his object of (unilateral) desire as the box is repeatedly punctured by Maleficent and company. Thus follows another hard reset of the story as the Prince charms his way into a telling of his version of the fantasy. It is narrated as “an Aurora who wants saving,” and is presented as the male fantasy contradiction of an experienced, sexually mature woman who is also lacking power (while literally bound at the wrists) and who requires childlike protection. This Aurora duets with each Beauty in turn before being carried off by the Prince. Kent’s duet with John Allen begins in struggle but features moments of lilting beauty, especially encapsulated by a swinging turn where her feet skim and glance off the ground in a dreamlike slow skip. Christine Hasegawa expertly twines with and directs Kent in a more dominant mode, and Ari Hasset brings a forceful tenderness to their duet. Aurora’s long velvety cuffs are then positioned over her eyes as a blindfold, with her elbows pointed upwards. This makes for a very interesting posture in her dancing with Nathan Shaw and Juan Carlos Claudio as well as underscoring her lack of free and informed choice.

After Princess Aurora is swept away, another abortive “happily ever after” is cut off by The Beauties, now clad in frilly frocks and silly tutus, skittering about and demanding their turn in the telling. By slumping against and running into the many cardboard boxes in a believably haphazard stupor, they in fact artfully rearrange the set pieces into a central cluster upstage. The Prince arrives to kiss them awake, with comically loud smacks, only for them to be repeatedly cursed by Maleficent, as heralded by the loud “snick” of the knife. It is a light treatment of the dark theme of the willing recidivism in The Beauties’ victim/perpetrator role. This cycle of drugging and waking escalates and intensifies until it comes to a head. The bodily manipulated John Allen and his repeated falls to the pillowed floor become untenably frantic, like something between Pina Bausch’s Café Müller and The Three Stooges. This built tension is capitalized on as the Prince and Maleficent forge a felt erotic bond in a charged look over the inert bodies they control. The two pair up and the narrator resignedly sighs something to the effect of “you two, of course, no, that makes perfect sense.” And moreso than any other moment, this one has been prefigured and developed; it perfectly does make sense.

Thereafter, as the audience can only have been eagerly anticipating throughout, Aurora takes her turn at directing the narrative centered on her experience. She voices and then enacts her own fantasy, bringing the show to its abrupt, violent conclusion.

The other book Brown cites as inspiration is Joan Gould’s Spinning Straw into Gold: What Fairy Tales Reveal About the Transformations in a Woman’s Life. It is a nonfiction exploration of fairytale as allegory for the breadth of the changing, lifelong experiences of womanhood. And though SB Dance presents strong and vital personalities across the gender spectrum, the central character of Aurora was not terribly developed. Rather, the multiple-narrative perspectives sacrificed her singular ontological continuity to the presentation of an object through multiple lenses. Annie Kent embodies Aurora completely and performs the role stunningly, but the role is object and naif. When she finally wrests back her agency (through engagement with the super-structural narrator, not her abusers), she enacts a brief and frenetic revenge fantasy à la Quentin Tarantino. Revenge fantasies make us feel the reward of redressing grievance, but don’t do the rhetorical work of conclusively addressing expository complexity. Sleeping Beauty features Kent as a performer but doesn’t center Aurora’s experience as a character.

I grant that the processing of trauma, confrontation and accountability of (living) abusers, complexity of emotional attachment, and complicities would make for a very different ending - one that is less of a campy-dark combo, more truly dark. And I’m not advocating for that alternative, necessarily. However, the presentational scaffolding of program notes, press releases, and interviews invite this expectation. A City Weekly profile indicates that Aurora’s character will be especially rich, and the ticketing blurb asserts a “#MeToo warp” to the classic tale. Organizations like Whistle While You Work (@whistle_whileyouwork) facilitate a platform for whistleblowing and providing resources for the dance and performing arts community to actively benefit from engagement with the #MeToo movement. While metacommentary doesn’t easily make a work artistically stronger or more enjoyable, when artists choose to reference social and political movements there is then a greater onus to address them responsibly and more fully. Not to do so then borders on appropriative. Sleeping Beauty beautifully and inventively updates a classic fairytale and peoples it with darkly compelling archetypes. But I did wonder if it intended to address or redress the entrenched misogyny that it identifies in the original.

In his program notes, Stephen Brown expresses gratitude to his truly fantastic group of co-creators with the witty neologism “WTF-people”, as in “WTF are you doing in Utah?” This is an example of the counter-cultural positioning that, as a non-native, I find intriguingly endemic to Salt Lakers. It implies both separation from Utah’s political and social establishment and affiliative solidarity with the subversive underground. But actually, and hopefully not to their chagrin, SB Dance is a pillar of the local arts community. Besides being a long-running successful company with lasting internal relationships and frequent new fruitful collaborations, they are teachers and college/university faculty, alumni of other longstanding dance institutions like Repertory Dance Theatre and Ririe-Woodbury Dance Company, and entrepreneurial arts therapists. Not least is artistic/executive director Stephen Brown, who creates programming connecting arts organizations, businesses, and local non-profits, such as Eat Drink SLC, and serves as president of the Performing Arts Coalition, which addresses arts and culture policy making, was instrumental in the needs assessment and creation of the Rose Wagner Performing Arts Center, and represents the Rose Wagner’s many performing companies in residence. In fact, less so than anarchic countercultural arts rebels (of which Salt Lake is certainly possessed of a few, like personal favorite Forbidden Fruits [@slcfruits]), SB Dance is very much a part of the fabric of the Salt Lake arts establishment. And as an innovative, sex-positive, broadly collaborative company, that is to the establishment’s benefit. Perhaps this bit of podunk posturing is an ironic understatement by an artist, producer, and organizer who in fact takes immense pride in the standing legacy and ever-growing stature of the Utah arts scene.

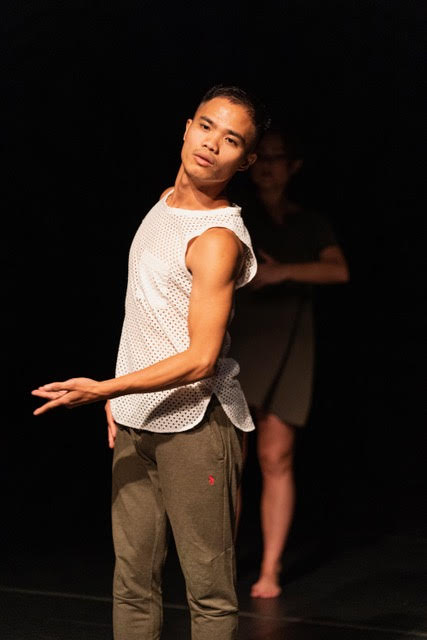

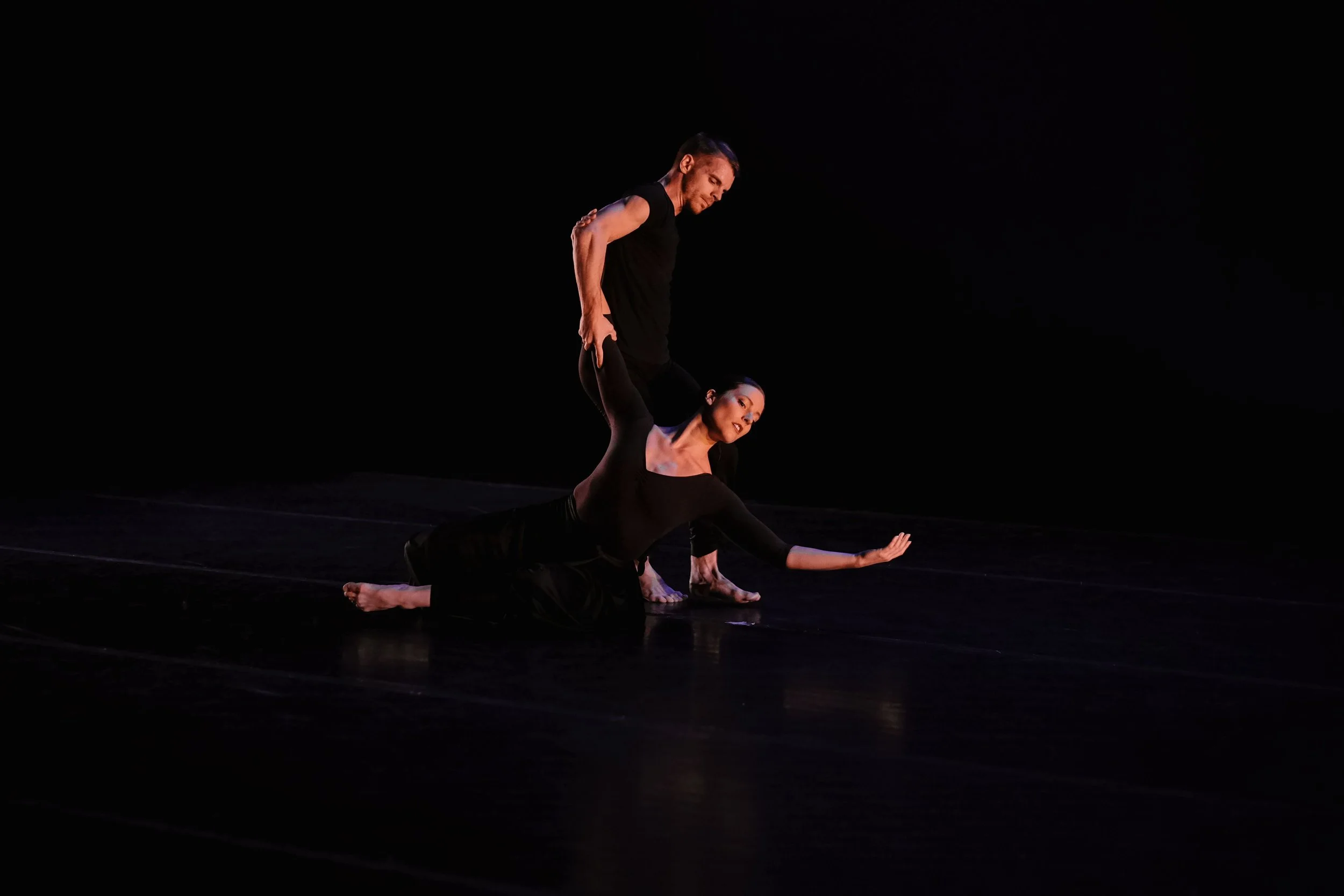

Photos at top: (left to right) of Nathan Shaw, Annie Kent, and Juan Carlos Claudio in SB Dance’s Sleeping Beauty, courtesy of SB Dance.

Nora Price is a Milwaukee native living and working in Salt Lake City. She can be seen performing with Durian Durian, an art band that combines post-punk music and contemporary dance.