Ballet West’s The Nutcracker is the first and longest-running full-length version of the ballet in the United States, created by company founder Willam Christensen in 1944 for the San Francisco Ballet. Legacy still features heavily in decisions made regarding the production and how it is marketed, and the continuity of the popular holiday classic is a point of pride for Ballet West (yet also somewhat of a sticking point). A costly overhaul of the production’s sets and costumes premiered last season with the firm reassurance that the choreography would go unchanged, and the resulting renovation has been well-received.

Tradition and historical precedent are often inescapable factors in the presentation of classical art forms. However, while familiarity and tradition may draw crowds to The Nutcracker whose sizes far surpass those at other productions, changes may be necessary to support the ballet’s continuation. In Ballet West’s production, a dramatic and deeply necessary alteration of the Chinese divertissement was made in 2013, although it was more cagily framed at the time and lacked clarity as to the nature of the need for change. Through the lens of 2018, however, the new Chinese dance is now just one on a wonderful and growing list of alterations made explicitly to end racial stereotypes in ballet. The Nutcracker, a major source of revenue for Ballet West and most ballet (and other) companies, provides the greatest visibility and exposure for an art form that struggles to be current and accessible. This means that the manner in which The Nutcracker represents ballet is even more critical.

The overture to Tchaikovsky’s suite creates an immediate wave of nostalgia the moment it begins. After a pleasant duration, lighting effects new to the 2017 version tastefully transitioned the audience into the theater experience by slowly and perfectly illuminating each of three ornaments depicting dancers that adorned the curtain. The matinee I attended was full of families with young children, who were audibly delighted by this display. Following the curtain’s rise, three successive orders of scale (the snowy town outside Dr. Drosselmeyer’s shop, the street outside the Stahlbaums’ manor, and the Stahlbaums’ front hall) were cleared before Act I began in earnest within the Stahlbaums’ home. As might be said of the entire first act, this felt somewhat tedious, but elements of traditional stagecraft helped relieve the protracted score. Additionally, a great degree of the charm throughout the first act’s party scene was imparted by the impressively well-rehearsed cast of children.

The endless social dances and toy-laden whirling were punctuated throughout the party scene by the convincingly precise and thoughtfully costumed Doll, danced by Kimberly Ballard, and the bombastic presence of Dr. Drosselmeyer. Drosselmeyer, portrayed by Trevor Naumann, was all sweeping iconic pantomime, sight gags, and emotive displays and his presence is critical to the enlivenment of Act I. Rather than the mysterious creepy uncle found in almost every other Nutcracker, Christensen’s flamboyant Drosselmeyer reminds me of the classic trope of the Eccentric Mentor. However, no amount of actorly interpretation could make his cape-swirling, clock-inhabiting presence less than sinister as a sleeping Clara begins to dream the battle scene. The Christmas tree grew in a very effective swirl of light, the battle ended after many alternations between cowering and saber-rattling, and Clara and the now life-size Nutcracker Prince were whisked off to take in the snow scene. The corps de ballet of Snowflakes was sharp, though anyone seated anywhere off center would have missed much of the clarity in their formations. The pas de deux was the first refreshing moment in the ballet to watch less than a full cast’s worth of dancers on stage and was a nice bit of classical partnering in its own right.

Following intermission, through some charming old-school puppetry, Clara and her escort arrived in the land of the Sugar Plum Fairy. The backdrop included an array of iconic world architectures, a kind of visual esperanto that brands universal goodwill. The intention was sweet but naively relativistic, the result troubling as ever given how these cultures are represented later in the second act. The welcoming Pages, danced by students of the Ballet West Academy, were amazing; they executed sequential double pirouettes and grand allegro jumps with confidence and skill. Their counterparts in the Ladies-in-Waiting were disappointingly mere stage-dressing, and overdressed at that, bearing cumbersome decorative staves and overwrought headdresses. All of which was very Old-World European in aspect… until the arrival of the costumed monkeys, dressed in fezzes and vests, who were cast-listed as “Servants” and whose mode of movement was a too-familiar servile, half-bowing trot. Act II had just begun and already I found myself questioning this young German girl’s grasp of the nuances of the Global Village and its neocolonial entanglements, herself and her worldly reverie poised on the cusp of the Second Industrial Revolution.

The entrance of the Sugar Plum Fairy was dramatic, a vision of beauty, strength, and composure. I could have done without the butterfly wings affixed temporarily to her back, but I could also see how the kids in the audience might have enjoyed them. Emily Adams was completely stunning in her Sugar Plum variation, articulating every inch of the iconic solo and the final pas de deux. The series of divertissements that preceded her were largely enjoyable. The Spanish divertissement was a fun and lively trio, the Mirlitons found ease in a technical ensemble, and the Russian dance was both crowd-pleasing and reflective of a folk dance tradition. The Waltz of the Flowers was busy yet lovely, and I would gladly watch Katherine Lawrence as the lead flower do beautiful battement battu down the diagonal at the expense of the many pressed high lifts, which were less exciting than her incredible execution.

Mother Buffoon was a delightfully overblown archetype of the “pantomime dame,” in the music hall mimesis drag tradition. I think more could be done with the role to honor that tradition, as was achieved so well in last season’s production of Sir Frederick Ashton’s Cinderella. Mother Buffoon’s divergent torso and borrowed pair of legs make for fantastic vaudeville and are great technical costuming at that. The tiny bumblebees’ costumes looked rather cheap in comparison, and it is anyone’s guess as to why they are in and out of her skirts, but there exists both historical and local precedent: the 1892 premiere of Petipa and Ivanov’s Nutcracker ended with a hive of dancing bees, and Christensen’s production now lives on in the Beehive State. The bees are also super cute.

The Chinese and Arabian dances were more troublesome than enjoyable for me. The Chinese dance formerly exemplified racist caricature and now, following its 2013 reworking, is a skillful display with an element of cultural celebration. The alteration was deeply necessary and I am appreciative of Artistic Director Adam Sklute’s initiative in making the change. I also appreciate his commentary on it, which appears in the Final Bow For Yellowface, an initiative spearheaded by the incredible New York City Ballet soloist and “rogue ballerina” Georgina Pazcoguin. The new Chinese Warrior dance was imported from an old San Francisco Ballet version, choreographed by Willam Christensen’s brother Lew, and thus historically tied to Ballet West’s production. However, despite this retroactive commitment to end yellowface, we saw quite a bit of it still in Ballet West’s performance of Stanton Welch’s Madame Butterfly in 2016.

I am concerned that, without a similar such alternative, the Arabian Dance will not get the reworking that it too absolutely needs. The admission that many of the divertissements are caricature and stereotype, but to varying degrees of insult, is worrisome. The Arabian dance includes the same sexist servility found in the former Chinese dance, with the Arabian female lead also utterly sexualized and exoticized, flailing her arms and gyrating in a way that is needlessly outside of keeping with the rest of the dance and utterly divergent from any national or ethnic folk dance tradition. Ballet West has recently exemplified commitment to representing diversity in ballet, supporting female choreographers, and engaging in cultural ambassadorship as a touring company. I am grateful to support a company that actively progresses ballet in the twenty-first century. I hope I can count on Ballet West to do no less than excise the remaining blithe racism in their historical production of The Nutcracker.

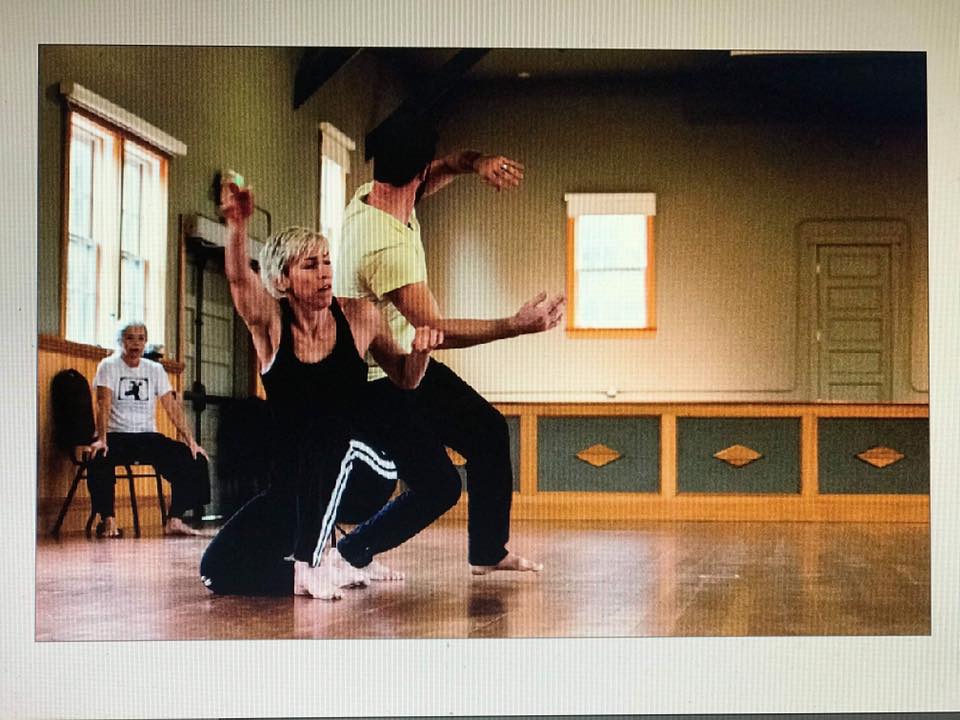

Nora Price is a Milwaukee native living and working in Salt Lake City. She can be seen performing with Municipal Ballet Co. and with Durian Durian, an art band that combines post-punk music and contemporary dance.