A few months ago, I sat down with Michael Watkiss and loveDANCEmore board president Ishmael Houston-Jones to talk about their separate lives as artist-teachers and their recent collaboration on the revival of Ishmael’s seminal 1986 piece Them at Performance Space New York. Them is one of the most important works of performance of the last few decades in New York. I’ve been keeping this interview on the back burner but now seemed as good a time as any to send it out as Them has just been named one of the top works of the year by the NY Times and Dance Magazine. Congratulations Ishmael and Mike!

Michael Watkiss and Alvaro Gonzalez in Ishmael Houston-Jones’ Them.

Samuel Hanson for loveDANCEmore: Thank you both for sitting down with me. Michael, what is it like for you to insert yourself into the history that Them represents? You were born in the eighties…

Michael Watkiss: I was born in the eighties in Salt Lake City, so literally culturally and geographically worlds away. Also, I am in this cast one of a minority of straight people, and so my own distance from the material is pretty significant. There is a quality for me which is very much about how the world shapes individual identity –– how where you are and what you’re dealing with shapes who you are. But I also think one of the great things about this piece is that although it was created in a very specific time and place, the themes are very universal, despite the fact that I’m different in many ways and my own experience is further away from where this piece comes from. Themes of alienation –– a desire and failure to connect, themes of sadness and fear particularly about death are very much universal. And so I didn’t have any personal trouble connecting to those –– some of the nuances of, for example, understanding cruising… the first time I did the piece in 2011, that was a concept that I wasn’t very familiar with, that was just a cultural difference. And so it required for me to understand that I was going to be listening a lot, to Chris [Cochrane, the composer] and Dennis [Cooper, who wrote the text] and Ishmael and the other cast mates and not to try to mediate their experiences through my own, but just be really open and receptive to them, if that makes some sense. And I think I did that with varying degrees of success over the years with different concepts in the piece. It’s easier this time also because I’m revisiting it.

Watkiss, Hentyle Yapp, and Alvaro Gonzalez

Sam: Ishmael, we were talking the other day about casting and how different people can upset or support the entire cast. How does Mike fit into this cast?

Ishmael Houston-Jones: It was funny, I first called Mike in 2011 in a panic because literally of the seven people, only three could do it. We got this gig right after the American Realness festival which Ben Pryor puts together. This presenter from the Netherlands said I want this piece and our festival is in three months. I had to find four people who could fit into this thing. And this piece is really intimate and involves a lot of vulnerability among the performers. Logistically it would have been much easier to find all people from New York, but I really needed a specific chemistry between the seven.

I chose Mike because I’d worked with him at ADF, he’d taken my class. He’d come to all the improv jams that I moderated, we had talked a lot together and I felt that he would understand it. And also Greg Holt who was from Philly, which was less of a logistical risk because Philly is closer, but still challenging. And then Steve May was from New York as was Ben Van Buren who danced alongside Felix Cruz, Niall Jones and Jeremy Pheiffer who were in all the tours from 2011 - 2014.

So, I really wanted Mike Watkiss, I just had this great memory of him at the American Dance Festival. I called him up and the first thing he said was, “but Ishmael, I’m straight,” and I said, “but Mike, it's a performance…”

Mike: Forgive my naiveté… [Laughter.]

Ishmael: I didn’t even understand the comment actually. It turns out he really works well in the role, that my instincts about Mike were really right on. I think he’s grown a lot in his knowledge understanding and the coloring of the work.

Even in that first one in 2011… which was really wonky because four of the people were literally brand new and put together in a couple of weeks of rehearsal which is just not the way this piece works, you need to get into each other’s heads and emotions, and without language and without set choreography, it is a really challenging piece to perform actually. But I was really right about Mike.

Sam: How did you approach casting this time?

Ishmael: I asked everyone who was in the original 2010 revival if they could do it and only Jeremy Pfieffer didn’t have other things, was living in the city and wasn’t injured. And I was really glad he could.

Alvaro Gonzalez, Michael Parmalee and Watkiss

And I really wanted someone else who’d been involved in the process because actually four weeks is a very short amount of time to put this thing together because there’s no set choreography and so much language and so you have really learn to improvise together in a very specific way. And in very different ways throughout the piece. And so I called Mike and all the 2010 guys of whom Jeremy was the only one who could do it. Mike had done it twice in Europe in Portier, France and in the Netherlands and over time too and I could see how he’d grown with the work.

Mike: Ishmael, you have just been lauded by one of the most legendarily nasty dance critics in the world [NY Times’ Alastair Macauley] as having created “one of the most powerful pieces of dance theater of our time.” What’s next?

Ishmael: I don’t know. I really don’t know. I want to make something new, it’s interesting the piece I mentioned earlier today that I made with Miguel Gutierrez, Variations on Themes from Lost and Found: Scenes from a Life and Other Works by John Bernd, the world’s longest title…

Mike: Still pretty a good one…

Ishmael: It’s a reimagining of the work of the choreographer John Bernd who died in 1988 of AIDS complications at age 35. I’d worked with him and been in three of his major pieces and a few other shorter ones. And the piece Miguel and I made was a mash up of his work, taking the last seven pieces he made in his life between 1981 and 1988, and putting them together…

I know that I want to get out of the eighties. I know the next thing that I do I really want not to be AIDS-related or eighties-related, just because I’ve done that really intensively for the the last few years with the Bernd piece and the various Them revivals, besides the one other new thing that I’ve made which was 13 Love Songs: dot dot dot, a duet with Emily Wexler.

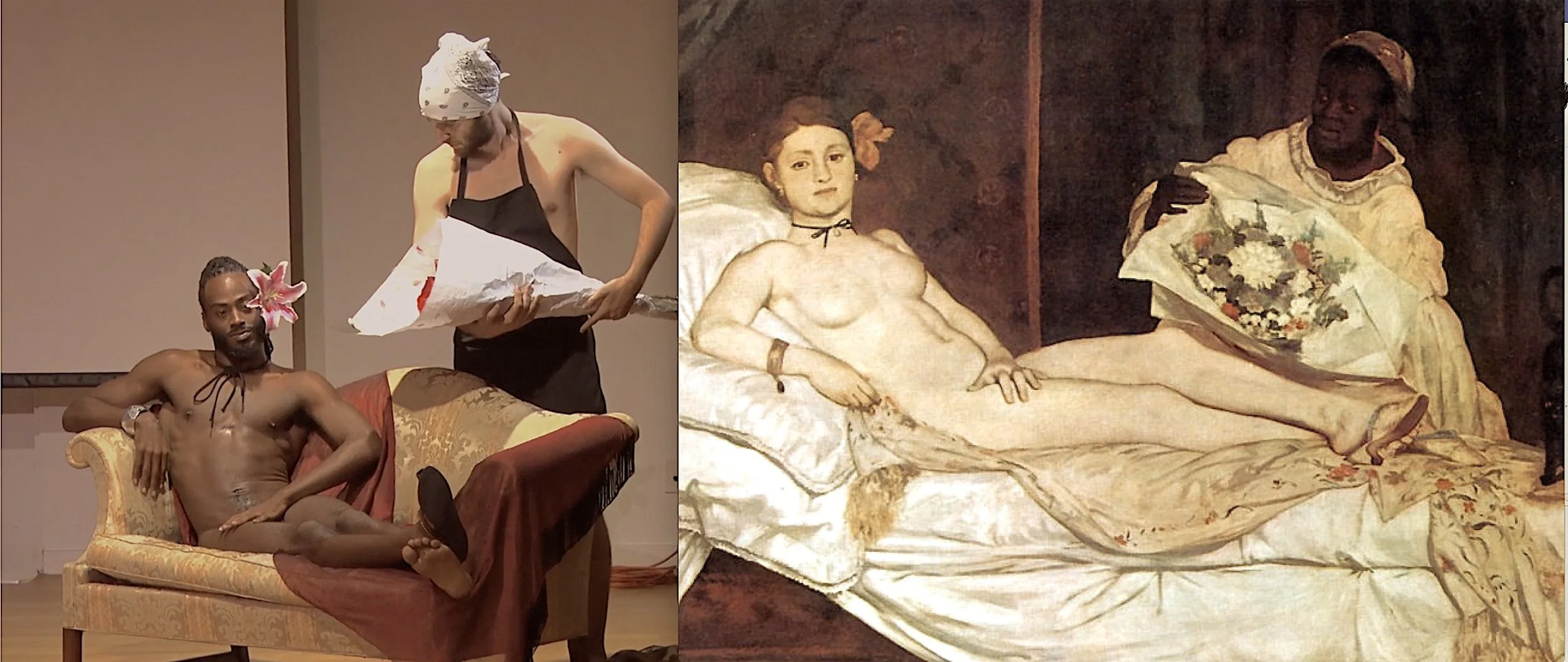

I’ve begun working on a concept, I actually started thinking about it years ago, my fascination with the Black maid in Manet painting Olympia and my search for who the model was. I sort of queered the image of the nude white woman being presented flowers by the dressed black maid behind her by having both models be male and having the black male be the reclining nude and having the white male be the one with the flowers.

Orlando Hunter takes the place of the white model in Ishmael’s reimagining of Manet.

I paired it with Nina Simone’s cover of “Pirate Jenny” from Three Penny Opera, and I went online and found images of maids from movies and television –– from Gone with the Wind, to The Jeffersons to The Help and Imitation of Life. And when I started the search… I mean there are hundreds… I mean, it’s a part of American culture this image of the Black maid. Sometimes they’re sassy, sometimes subservient, sometimes the helper, but anyway it’s such a trope. And I’m wondering what happens if you queer that trope, what happens if they’re male, what happens if they’re Asian, what happens if they’re Trans?

Mike: How does that change the perception…

Ishmael: Yeah, so I am thinking it might not be a performance. It might be an installation, maybe in a museum. I’m gonna keep working on it this year…

Mike: I think it’s also worth mentioning that Ishmael just published his first book FAT and other stories…

Ishmael: Yeah. A lot of it is just old writing that’s been on my hard drive for a really long time. There is sort of a theme of sex and so I though it would be fun to just get it all out. I want to write about dance and improvisation and minorities and people of color and how those worlds intersect. But I’ve actually never put a book together and so I thought this might be easier to start with since most of the writing was pre-existing and just needed a lot of editing.

I worked with Ben Van Buren who’d been a student of mine at the New School but he also did a couple of versions of Them abroad. And he’s now set up a publishing company called Yonkers International Press. So, I asked him if he would help me get this out and he was really helpful and it looks really good.

Mike: Yeah, it’s wonderful.

Ishmael: So, I think I have a handle now on how to get a book together and so I want to write about dance teaching, performing and improvisation. And how improvisation as I know it, the forms I know, intersect with people of color. [Ishmael was just down in Florida at the Robert Rauschenberg Residency working on this…]

Mike: It seems like both in your writing and your choreographic career you’ve had this view into the past and somehow you’ve managed to get past it, expel it. And now you’re looking toward the future…

Sam: And you Michael?

Mike: I don’t know. I recently founded a dance theater, specifically Butoh company with some friends of mine in Salt Lake City. I’m not sure if I am going to continue to work in that frame. I hope to do so. I’m also just beginning to experiment with playwriting so I hope to do a great deal more with that.

During this process, I’ve been thinking very much about flexible theatrical structures, in the way that Them is a very well constructed theatrical structure. It’s a series of scores that are very well constructed and considered, assembled to perform a certain action. I am wondering if there are possibilities involving more theatrical elements. You could have a play, for example, that involved two characters but their relationship could change every night depending on –– I was thinking of doing something as straight random as a game of chance or a roll of the dice, but maybe there's a monologue that one of the characters has to deliver before the end of the first scene, or a conversation that takes place in the second scene that is written but the performers have to improvise their way to that somehow and they do that perhaps angrily one night depending on the game of chance or lovingly the next night, something like that which does what the structures that you’ve created do but uses slightly different elements. And of course I am still very interested in choreographing so it will definitely have movement in it, but i am very interested in how to use improvisational techniques more broadly, applying them more broadly.

Sam: I think of both of you as teachers of improvisation working outside of the mainstream of dance, what are your teaching strategies and how are they evolving?

Mike: I’ll go first because I probably have a lot less to say as I’ve been teaching a lot less, for many fewer years than Ishmael. I think one of the things that makes Ishmael such a good teacher is that he is never interested in leading you to something particular, at least in my experience, he has never said “do it this way,” or “don’t do this.” He limits the options you have but he never proscribes what the answer is. And in a way he’s just constantly asking you questions. He has an amazing way of making you feel safe, safe enough to really go deep within your self to answer those questions.

I think that quality of honest is what I identify with his work –– literary, choreographic –– and incidentally I think that’s why this piece has been so well received. That quality of honesty is very resonant. And so in my own teaching, which I have not done that much of, I think I try and emulate that to a degree. I try to ask questions which are open-ended when I think maybe people are reasoning in a direction which is going to be less constructive or lead them into dead ends…

At the same time, I try not to be proscriptive. I try not to tell people what to do, because that’s very limiting. I think we’ve all had teachers who try to tell you the right answer and you don’t –– at least I don’t –– retain it will if I’m just told the answer. If I’m encouraged to find the answer in the right way, in which I can apply my own answer, that sticks with me much more.

Ishmael: That’s true; you articulated my vision better than I can probably.

I like setting up situations. I like entertaining myself. I like making people do things that I like watching or being involved in. I very rarely plan my classes, I usually walk into a room and feel what’s there. I mean I usually have some vague idea of the material I want to get through. For example, at a university, by the end of the semester there are points that I want to have covered, but there’s sort of, not an order to that. I try to be informed by the people in the room with me.

At the University of the Arts in Philadelphia, the last time I was there in the fall I was teaching two classes back to back of the same material, which was really difficult for me because the first class I would just come in and do it and then with the second class I felt like I had to repeat myself and sometimes I would just not do it because they were different people, different times of day, coming from different places, different interpersonal dynamics. So it was really hard to teach that second class because it really went against my feeling. I really felt like I was expected to teach the same material to both sections and it didn’t click til later that that was the problem. That was what made my teaching in the second class fall flat.

I'm not proscriptive, I like setting up situations, I like surprising students and I like — in terms of improvisation — having them watch each other and being able to critique, not nasty critique, but just really articulate what they see and how to begin to find language around that. And some of them make shit up but some really find language around it, this actually helps them form how they approach improvisation.

It’s interesting that as I’ve aged I dance less in my classes. I had a medical issue in 2013 so when I went to ADF that year I took an assistant who did all of my demonstrations because I’d just had surgery and I wasn’t supposed to lift. And that changed thing, I don’t necessarily think for the better…

I noticed at the beginning of working on Them this last time –– in the warm-up –– I didn’t dance with people so much. But in the performance weeks because I had to dance at the beginning, I actually did warm up with people and it felt better and I think it did shift something in the performance of the other dancer actually.

Mike: I agree, not that I think that I could tell you exactly what that was.

Ishmael: It was something different about me being there for the half hour before the performance, Chris playing, me out there with you guys, and doing contact.

Mike: And Dennis out there improvising language for us to work with!

Sam: Did he really improvise language for rehearsal?

Mike: Yes, definitely for the warm up, yes, sometimes it was just collages of song lyrics or –– it was amazing, fantastic…

Ishmael, Kensaku Shinohara (blindfolded), Jeremy Pheiffer

Ishmael, Can I ask just a slight follow up question? This is just based on a conversation I had when I had just arrived here in New York for this rehearsal process. You said to me that you didn’t imagine yourself being a teacher when you began or that that was not the central aim…

Ishmael: When I was in Philly with Terry Fox, who was one of my mentors, we taught but we didn’t make any money off of it. People would show up in Terry’s loft in Old City and we would just sort of jam around –– her boyfriend at the time Jeff Caine was a musician –– and do some exercises.

But when I moved to New York and realized that I didn’t want to do restaurant work anymore, I did start teaching. I think I always enjoyed it but I had the idea that I was only doing it for the money. And its been recent actually that there's been a turning and it might just be a maturing in me, that this is something that I really do that is essentially a part of what I do as an artist –– I teach, I mentor, its important and I should focus on it. I mean –– A. I don’t make that much money doing it––

[Laughter]

A little bit but not a lot. I’m a constant adjunct at places like the University of the Arts, NYU, the New School. I realize that I actually do like imparting this, molding this, especially around dance because there’s a lot of bad improv and teaching that I’m critical of going around… and I really like exposing younger dancers to a different way of improvising…

Mike: You’ve created quite a legacy for yourself and I don’t think I’m the only person who feels that you’ve really changed the way we think about how dance is made and what it can be.

Sam: It’s interesting to talk the two of you, because you [Ishmael} came up in an era when –– I mean you did go to [the] Gallatin [independent study division of NYU] and you did go to to Gannon [College in Erie, PA], was there any dance at Gannon…

Ishmael: There was no dance, we did a little street theater, I did student pieces in theater where I was cast because I could dance…

Sam: It seems like in Philly you weren’t taking much formal class.

Ishmael: That’s not exactly true. When I moved to Philadelphia when I got back from a year travelling in Europe, I was taking a lot of class at Temple, a lot! I never enrolled, but back then because I was a man they just let me audit unofficially.

Sam: And you even didn’t have to pay.

Ishmael: No, and I studied with Helmut Gottschild and Eva Gholson, I took one semester of ballet. There was the Arthur Hall Afro-American Dance Ensemble where I took Afro-Carribean and Joan Kerr who had been in the Horton company, and Contact with John Gamble… so, yeah, I took class!

Sam: I imagined you taking class in New York and maybe that’s one of those things about my generation is that we romanticize the idea of taking class in New York as apposed to at University. Whereas Mike and I went to the U…

Ishmael: I was never in a dance department. I was taking classes at Temple but also taking classes at Group Motion which is the only company I’ve ever danced in, and I was traveling around…

Sam: I guess what I am trying to get at is this. Are the two of you optimistic about American dance is happening in terms of training and its evolving relationship to the university?

Ishmael: It’s weird because I think, talking specifically about Them, and looking at the audition videos, dancers’ physical facility is many times greater than it was in the eighties. Then people were interesting dancers and movers and were probably closer to the raw emotionality of the piece but what dancers in this version can do is really outstanding. Particularly Hentyle Yapp and Johnnie Cruise Mercer…

Hentyle Yapp being lifted by Johnnie Cruise Mercer

Mike: Both physically and emotionally just unbelievable dancers…

Ishmael: Yeah and that came through university training. They do things that I could never have done, even at their age, so there’s that positive. The emotionality in the work that I’m interested in both making and seeing doesn’t have to do with that. But it’s great to have dancers with that facility as long as they can also get there. And at a lot of dance programs, what ever that intangible otherness is, it isn’t taught or valued, so you get these people with incredible facility –– at the audition for example half of the people could have done the stuff physically…

Mike: If not sixty or seventy percent, clearly…

Ishmael: But to tap into that emotional vulnerability and openness, it would have taken a year to beat it out of them.

Mike: My perspective is much more limited. I’ve only attended one dance department and I teach in the theater department [at the University of Utah]. I think I would echo a lot what Ishmael just said. I think technical facility in any art form is invaluable in that it increases the range of things that can be expressed. There are certain things only be expressed by putting your leg up at a ninety degree angle, so the ability to use that as a tool… but, and this is the limited critique I will give of the U[’s dance program], if you are not ever taught to investigate your own aesthetics or develop your own curiosity or your own ability to think about what you’re seeing and the world at large and how you synthesize ideas into art that is honest and dynamic, then all of that technical ability goes to waste. You can say a lot, but you have nothing to say.

That’s what’s so amazing about all three of the original artists of Them. That’s what’s so amazing about Dennis and Chris and Ishmael, is that you guys all have this incredible innate understanding of your own aesthetic and a desire to express it and your creative vision in a way that is ground breaking. I think it’s fair to say that you three do things with your chosen media that I have just not really seen. I don’t know if you guys think that’s fair…

Sam: I certainly agree with that.