At 7:24 p.m., I stepped into the Jeanne Wagner Theatre for SALT Contemporary Dance’s 7:30 p.m. Spring Concert, to find dancers already onstage. I felt slightly guilty walking in during a performance, but other audience members were doing the same, and I heard whispers about this being the pre-show.

Some of SALT’s key branding points are that they are the second largest dance company in Salt Lake (now encompassing SALT and SALT II, as well as a junior and senior company for ages 12-18), and that they are bringing new, cutting-edge dance to Utah. I was glad to see their senior company perform (if only briefly this time), and would be interested to see the junior company at some point too.

After finishing a piece choreographed by SALT company member Logan McGill, the senior company took their bow, and then crawled backward to stand up and take a smaller bow, which I thought was a nice detail.

After a pause right at 7:30 p.m., “Stand by Me,” the first main company piece, began with the house lights still on. The stage was littered with a hundred oranges, and two dancers began slowly and carefully rolling one between their bodies. It was absolutely beautiful and unique, and accompanied by peaceful, pleasant music that helped set the tone. At a V.I.P. event the previous week, Spanish choreographer Gustavo Ramirez Sansano mentioned he was inspired by a game that children play with oranges in his home country.

After this had gone on for a while, more couples joined the scene, and the house lights dimmed. A sense of loss was palpable when one half of a couple abruptly left, neglecting the orange and letting it drop to the floor. It made me think of the Spanish phrase “media naranja,” which translates literally to “half orange” and refers to a concept similar to “my other half” or “you complete me.”

After another pause, SALT II performed “I Love You,” by Portland-based artist Katie Scherman. The dancers impressed me with their fluidity and control. They looked like they had been training hard, and training smart, since I last saw them in concert this past fall. It was also a somewhat different group than previously.

I loved the gesture phrases in “I Love You,” including some heart-shaped hands. I was impressed with the execution of wavy shoulder moves, and of a solo with a lengthy balance following a one-footed élevé.

“Beyond the Limitation,” by Joni McDonald and SALT artists, premiered last fall and was reworked a bit for this presentation. This time, the music was more unique and the intention seemed clearer.

In the fall, there had been three couples doing the same choreography at the same time for some parts, but this time, there were two couples for the most part who took turns dancing (the stage-right couple moved for a bit while the stage-left couple sat still in the dark, and then the lighting drew attention to the stage-left couple’s movement, as stage-right darkened).

The first time I saw it, the intent of the piece had been unclear beyond a heaviness in personal interaction. This time, I noticed distinctly that there were moments of missed connection, which I found very interesting. For example, one dancer would reach for another just as she was moving out of the space within which he would have been able to touch her. McDonald is absolutely brilliant at partner work, and I’m so glad that she was able to continue to explore this piece.

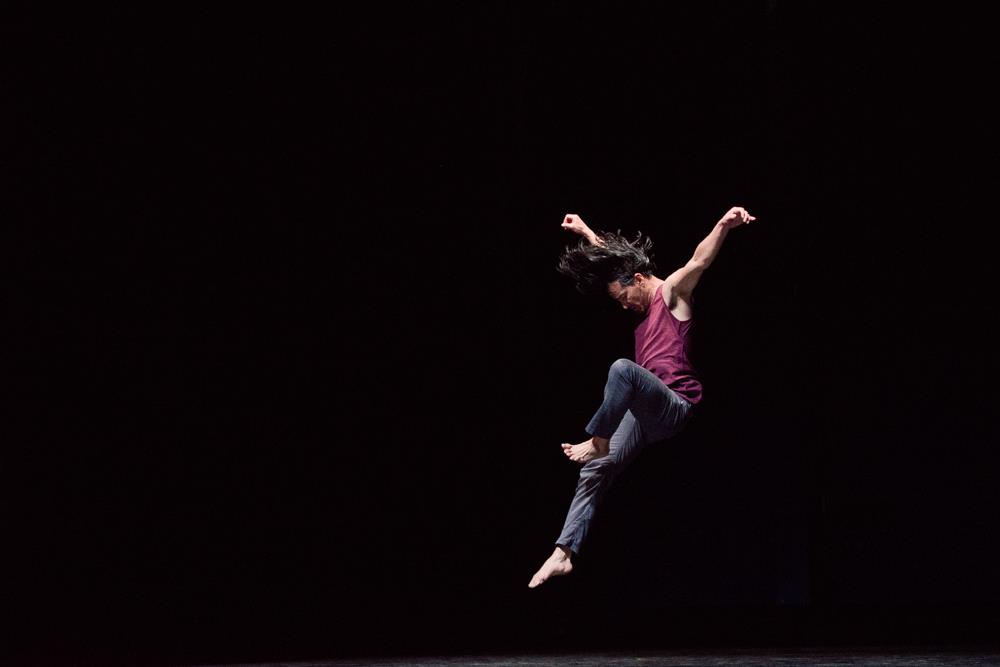

Following an intermission, Eric Handman’s “Cloudrunner” showcased intricate, group-interactive choreography. Some of the phrases were repeated facing different directions, a choreographic technique that can be tiresome, but that in this case stayed exciting, allowing the audience to notice different aspects of what took place each time.

I particularly enjoyed when two female dancers lifted Eldon Johnson off the ground, his arms over their shoulders, and Johnson pantomimed running in mid-air – which tied into the piece's title for me. I also always appreciate when dancers who are not the smallest onstage are lifted – when the group makes something work without doing it the easiest way.

The final piece of the concert was “Proverb,” by Banning Bouldin, which was memorable for the well-utilized costuming of nude bodysuits and long, sheer, puffy black skirts. According to the choreographer’s program notes and a previous conversation with Johnson, the skirts represented the weight of regrets the dancers carried with them. The movement was appropriately heavy for this theme.

For me, the most striking image in this piece was when Arianna Brunell took on an extra-immense skirt of regrets, built up underneath her by the other dancers whose shoulders she sat on, with everyone’s skirts trailing out behind her in a long train.

By the end, all the dancers had shed their skirts/regrets, which, knowing the intended symbolism, was something I was really hoping would happen. Johnson kept his skirt on the longest, and I could see his relative heaviness as he interacted with the skirtless dancers toward the end.

The piece finished with a repetition of Brunell’s extra-immense regrets shape, only without the skirts this time. The tone was still somber, although I had hoped that the dancers would feel lighter without the weight of their skirts. But maybe the similarity could show that you never know just by looking at someone what they might be carrying around with them.

Overall, SALT’s Spring Concert presented a great collection of well-executed choreography with interesting concepts and unique visuals. I look forward to enjoying more from SALT in the future.

Kendall Fischer is artistic director of Myriad Dance Company, for whom she also choreographs and performs. She performed with a variety of local groups, including Voodoo Productions, SBDance, Municipal Ballet Co., and La Rouge Entertainment. In 2017, Kendall’s dance film project, “Breathing Sky,” received the Alfred Lambourne Prize for movement.