The preview performance of SNaked was assuredly like a first kiss — reeling in various exciting directions, sometimes disjointed with a limited scope, but consistently provocative and engaging. Before the lights dimmed, SB Dance artistic and executive director Stephen Brown thanked the audience for offering a preliminary “pucker”—payment for a ticket of the same price as the polished show coming June 10-11 and 17-18, a monetary vote of confidence that many performance companies need to stay afloat.

SB Dance patrons are promised a night of fervent subversion at the company’s events, usually intended for a liberal population concerned with bolstering Salt Lake City’s’s coveted counterculture. Acknowledging the origin of Salt Lake’s counterculture has become a local platitude, one that SB Dance preserves, but also pokes fun at. This tension between conservative ideals upheld in the LDS Church and their antithesis upheld by the white “counterculture cult” is intriguing, but limiting. It risks erasing the diverse population of people on the fringe, including many people of color, or queer people who don’t fit the “respectable” white, cis gay male bill that other white cisgendered people can more easily sympathize with and defend. Being of this latter group, Brown creates work that is more likely to represent that mainstream population, especially because of his executive direction style — his choreographic and directorial vision is clear and crisp, uncompromised by very much collaboration save for that of associate director Winnie Wood. Nevertheless, the dynamic and kinetic nature of SB’s dance circus provides a refreshing bit of nuance on themes like gay rights and culture, the role of art, and, in the case of SNaked, a playful critique of patriarchy in Christianity contextualized within capitalism.

Following Brown’s opening remarks, a projection of the universe appears on the curtains, each galaxy pulsing to the voice of Winnie Wood, creating a delightfully simple personification. The female universe is stressed out about new galaxies that have formed since the Big Bang—she has a lot to orchestrate—so she decides to take a bath; she adds water, and fresh air, and, as a way of finding joy amid the stress of being the universe, also decides to add some children (played by Annie Kent, Christine Hasegawa, John Allen, Rick Santizo, Florian Alberge, and Kimberly Campa). They move powerfully across the floor, which is covered in what seem like wood chips, each performer rolling, jumping, falling with a childlike disposition — unrefined, teetering, legs wide most of the time. They wear Baroque-style white wigs, creating a cartoonish effect along with their varied short white dresses and black boots. The universe mother soon discovers that these children need a supervisor – enter Nathan Shaw, supercilious and ready for some fun…or a hot guy to play with.

After a jazzy and sharp dance number starring Shaw as the fierce dominant figure watching over the children, cut back to Mother Universe, getting bored. Enter the voice of God, spoken by Stephen Brown. The Christian God is portrayed as an enterprising crackpot wanting a piece of the universe pie. He tries to prove himself to Mother Universe, describing his plans for a garden. Listing his attributes, he admits to being sometimes misogynistic, a piece of exposition that might have been better revealed as part of the storyline — the hesitancy to include misogynistic subject matter, even as a joke, for fear of reinforcing that which is being critiqued, is understandable, but in this case it would have been safe to include those comments, considering how they could have been critiqued by Mother Universe; alternately, there was no such discretion taken when the snake joked about enticing gorgeous black men, using the phrase “black ebony hunks.”

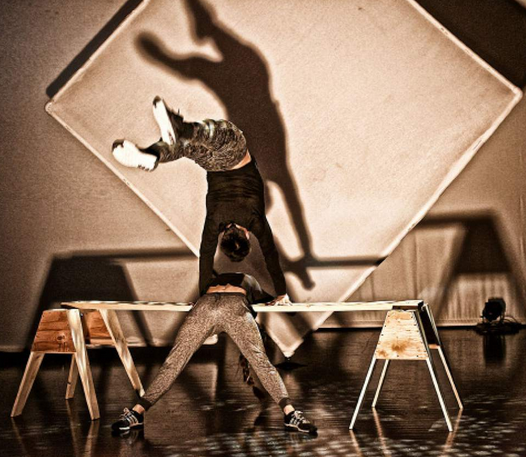

The show develops with the momentum of acrobatic movement sequences interspersed with cameos concerning the daily grind of living; the dancers hastily hump the ground, then they eat wood chips from wooden salad bowls, they go to sleep, and repeat. Garden of Eden Inc. is established with Natosha Washington playing Eve, confident, but out of the loop, and Florian Alberge playing Adam, portrayed as a cocky young CEO-type. Their performances feature a rhythmic stomping sequence by Washington and her crew of human-children, contrasted by an explosive solo by Alberge done to the song, “Taking Care of Business.” His torso-based turns, dips and shivers propel him from upstage to downstage and back up again as his obtuse character becomes even more so with his new position of power. Eve continually questions his power, but is also subject to it, as Adam waltzes her away from the apple that inevitably gets eaten by you-know-who, prompting their rejection from the garden and into the rough urban environment represented by projections of New York City, the other Big Apple. The rest of the tale is history, but the dance circus holds a few new twists worth experiencing this weekend or next.

Because Genesis is such a fundamental story, triggering myriad associations in a highly charged religious and political environment, and potentially warranting an entire deconstruction of western culture, particularly in the global north, creating or engaging with a piece like SNaked is no easy task. SB Dance is to be commended for taking another bite out of this apple of a subject.

Emma Wilson is a recent graduate of the University of Utah with a BFA in Modern dance and a minor in Environmental Studies as well as in Portuguese and Brazilian Studies. She has written for loveDANCEMORE along with 15Bytes and creates socially and environmentally engaged dance-theater work.